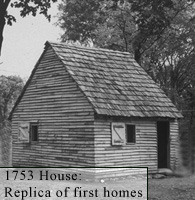

The 1753 House

in the Rotary

In 1750, village lots in the newly surveyed West Hoosac plantation were first offered for sale by the General Court of Massachusetts Bay Colony. The Court probably had two motives in establishing the plantation: to settle and fortify the northwest corner of the colony, lying along a heavily used Indian path (now called the Mohawk Trail), and thereby protect towns to the east and south; and to prevent Dutch settlers in New York from inching over their eastern boundary into Massachusetts. The area was a heavily forested wilderness and, although some of the lots were purchased by speculators, many were acquired by soldiers from Fort Massachusetts — four miles to the east — the last outpost on the northern line of defense during the French and Indian wars.

In 1753 the General Court ordered that settlers were required to build a home on their land. The regulations stated that in order to gain title to a lot, settlers were required to clear five acres and construct a house measuring at least 15 by 18 feet with a 7 foot stud, and a chimney. It was these requirements that gave the name “regulation house” to these early buildings. It was the intention of the government that these permanent houses would provide a basic structure to live in that could easily be expanded to make a larger building. Two men helping each other could build two regulation houses in three to four months. The first meeting of the Proprietors took place on December 5, 1753, at which time there were about a dozen frame “regulation” houses along what is now West Main Street.

The early years were difficult for the settlers. The French and Indian War brought fear of ambush, scalping, and arson, and in 1756 a blockhouse and stockade, known as Fort West Hoosac, were built at the site of the present Williams Inn, as a refuge from repeated Indian raids.

After 1760, with the coming of peace, settlers flooded in, principally from Connecticut. Land was cleared and agriculture became the main source of livelihood. More land farther east on Main Street was divided and cleared, some roads were cut, and farming became the dominant way of life in the valley. Small saw, grist, and fulling (cloth making) mills were built. Professionals and craftsmen began to arrive: a doctor, a lawyer, cobblers, carpenters, blacksmiths, and shopkeepers.

In 1765 West Hoosac was incorporated as Williamstown. It was named for Col. Ephraim Williams who had commanded the northern line of defense and who, in his will, left money for the founding of a free school in West Hoosac, provided that the name of the settlement be changed to Williamstown. The school opened in 1791 and became Williams College in 1793.

In 1953, during the town bicentennial, a group of people determined to build a replica of these regulation houses, and using only tools and practices that would have been used to make the original houses, constructed the house you see on Field Park today. It belongs to the Williamstown Historic Museum and is known simply as the “1753 House”.