We bet this week’s historical marker will be puzzling to folks for many reasons. Where was Seth Hudson’s house? Who was Seth Hudson? Who were our first settlers? Who were the West Hoosac Proprietors?

And, most importantly, what is/was a Proprietor?

Here’s what Roy Hidemichi Akagi said in The Town Proprietors of the New England Colonies (1924, University of Pennsylvania Press) which is still the authoritative work on this topic.

“[In 1753] the majority of land grants from the General Court of the Massachusetts Bay Colony were made to groups or communities for the purpose of the formation of new plantations and townships. The grantees of these township and plantation grants became known as the proprietors.

These grants gave to the proprietors both necessary ownership and local government powers. This meant that the next stage in the evolution of title was grants from the town proprietors.

Originally, there was no difference between the town and the proprietors, so that a grant from the town was a grant from the proprietors. But as the towns grew and persons who were not among the original grantees of the township came to live in the town, a difference arose between those having the right to vote as to town administration and business affairs and those who had ownership rights in the town lands.

Gradually a separation occurred and the proprietors claimed the exclusive right to convey the land belonging to the original grantees. With their organization as an independent body, they rather than the town members, exercised jurisdiction over the common and undivided lands in any township.”

If you are interested to read further, Akagi’s book is available as a free, downloadable PDF here:The Town Proprietors of the New England Colonies

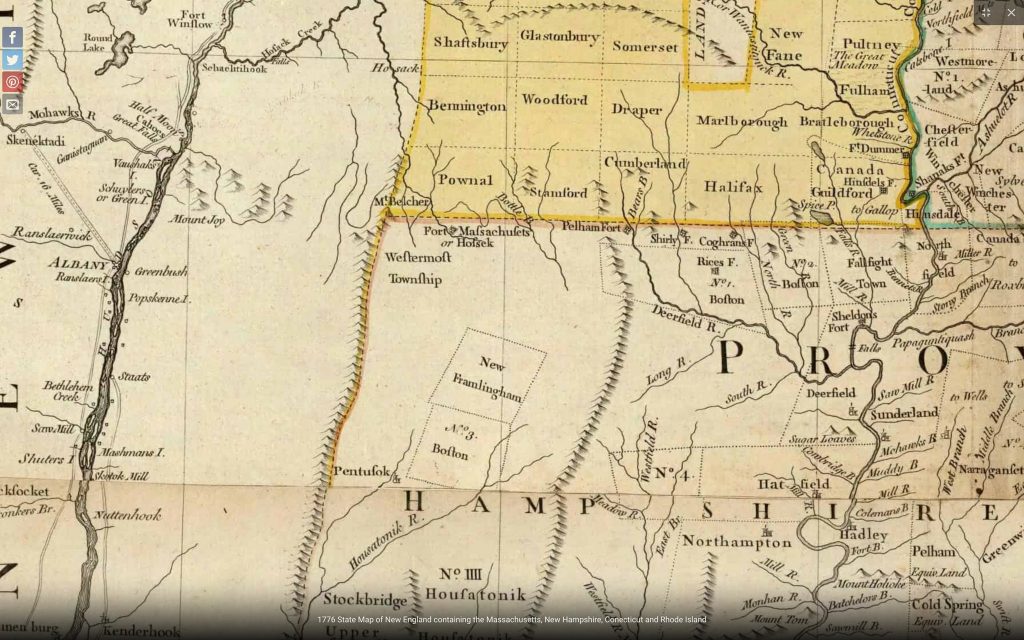

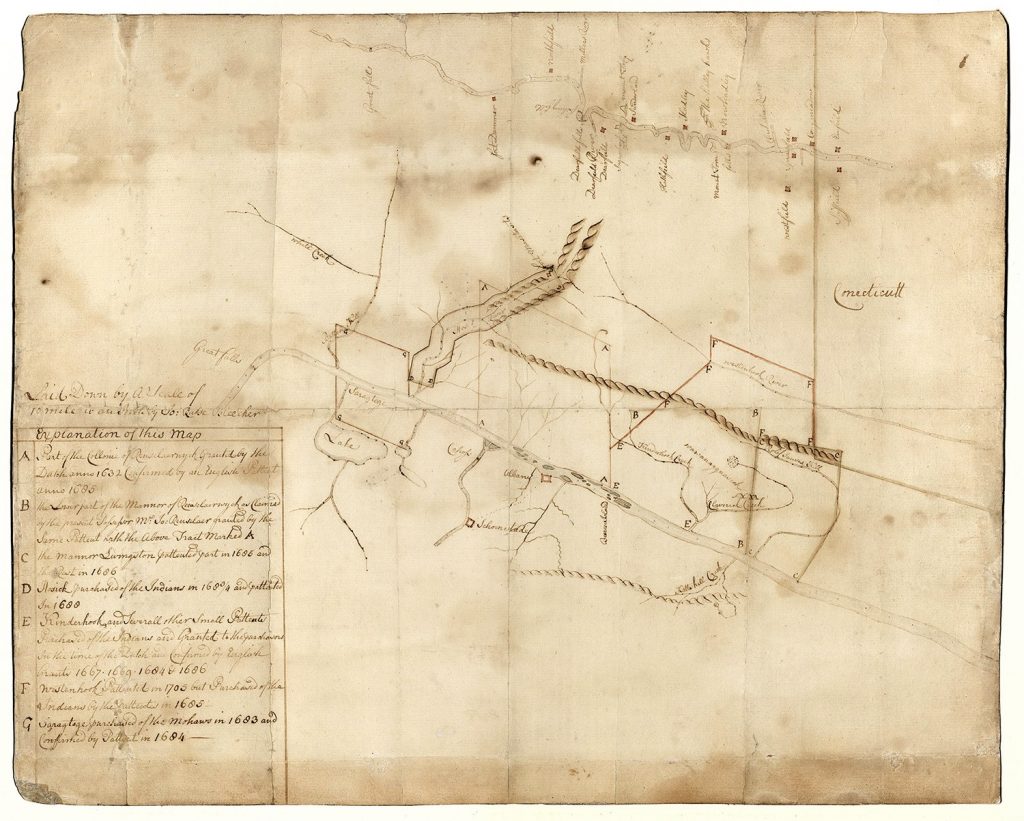

A close up from the 1776 map of our region in Jeffrey’s “The American Atlas: Or, A Geographical Description Of The Whole Continent Of America.”

Who were the West Hoosuck/Hoosac proprietors?

According to Arthur Latham Perry in “Williamstown and Williams College,” 1899″

“…on the 10th of September, 1753, the House of Representatives at Boston voted that William Williams [of Pittsfield, first cousin once removed of Ephraim Williams], “one of his Majesty’s justices of the peace for the County of Hampshire [it was eight years later when Berkshire County was set off], issue his warrant for calling a meeting of the proprietors of the west township of Hoosac so-called…

This vote was concurred in by Governor [William] Shirley and the Council the same day ; and on November 15, 1753, [Williams] issued his warrant to Isaac Wyman of West Hoosac, requiring him “to notify and warn the proprietors of said township that they assemble at the house of Mr. Seth Hudson in said township on Wednesday, the fifth day of December next at nine of the clock in the forenoon to act”…

Such meeting was accordingly holden at that time and place, and inaugurated a successful local self-government, which continued for twelve years the sole authority within “the west township of Hoosac.”

Portrait of William Shirley (1694-1771),

colonial governor of the Province of Massachusetts Bay

by Thomas Hudson, 1750, from the National Portrait Gallery

The proprietors mentioned by name in the record of their first meeting…are : Allen Curtis, Seth Hudson, Isaac Wyman, Jonathan Meacham, Ezekiel Foster, Jabez Warren, Samuel Taylor, Gideon Warren, Thomas Train, Josiah Dean, Ebenezer Graves, — eleven [white] men.

With the exception of Allen Curtis, who was the moderator of the meeting, and who not very long after returned to his former prominent position as a citizen in Canaan, Connecticut, all these had been soldiers in Fort Massachusetts before and all took military service in some form when the French War broke out again in 1754.”

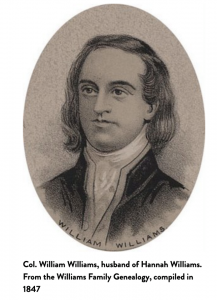

Etching of Colonel William Williams (1710-1785)

Thanks to Patricia Leach and The Clark Art Institute for this glimpse of the West Hoosuck Proprietors’ Book and a surveyor’s chain.

“The organization of a village and government had been approved on September 10, 1753, and a meeting of the proprietors was called to ‘determine upon a division of land or part of the lands in said township.’

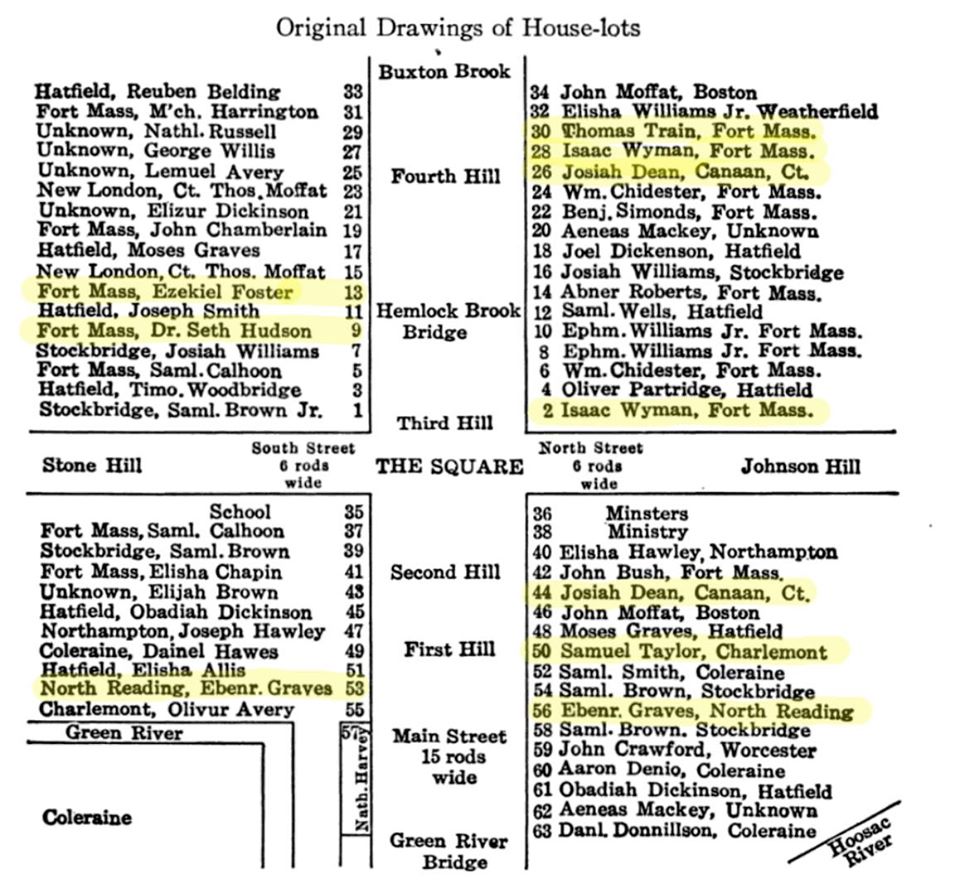

Over the course of years to come, lands were divided many times and in a number of ways. About a quarter of the first lots were offered to soldiers from Fort Massachusetts in lieu of pay in cash, while many others were sold via lottery in the eastern part of the bay colony. Some of the other first lots were sold to settlers from Canaan, Wethersfield, and New London, Connecticut.

Further divisions of lands were devised to equitably allot the natural resources of the township so that each of the proprietors received a share of fresh meadowland, prime agricultural land, other agricultural lands, pine woodlot, oak woodlot, and forested land on steep slopes.

Lots were measured using a surveyor’s chain, and the measurements were recorded in this book.”

Audio File of Pat Leach’s excerpt on the surveyor’s chain.

You can learn more about the exhibit that included the surveyor’s chain here:

Clark Art Sensing Place Exhibit

Let’s meet the eleven white men who were the Proprietors of West Hoosuck at the first meeting in December, 1753. In 1753 the Massachusetts Bay Colony would only allow white men to own land in its boundaries.

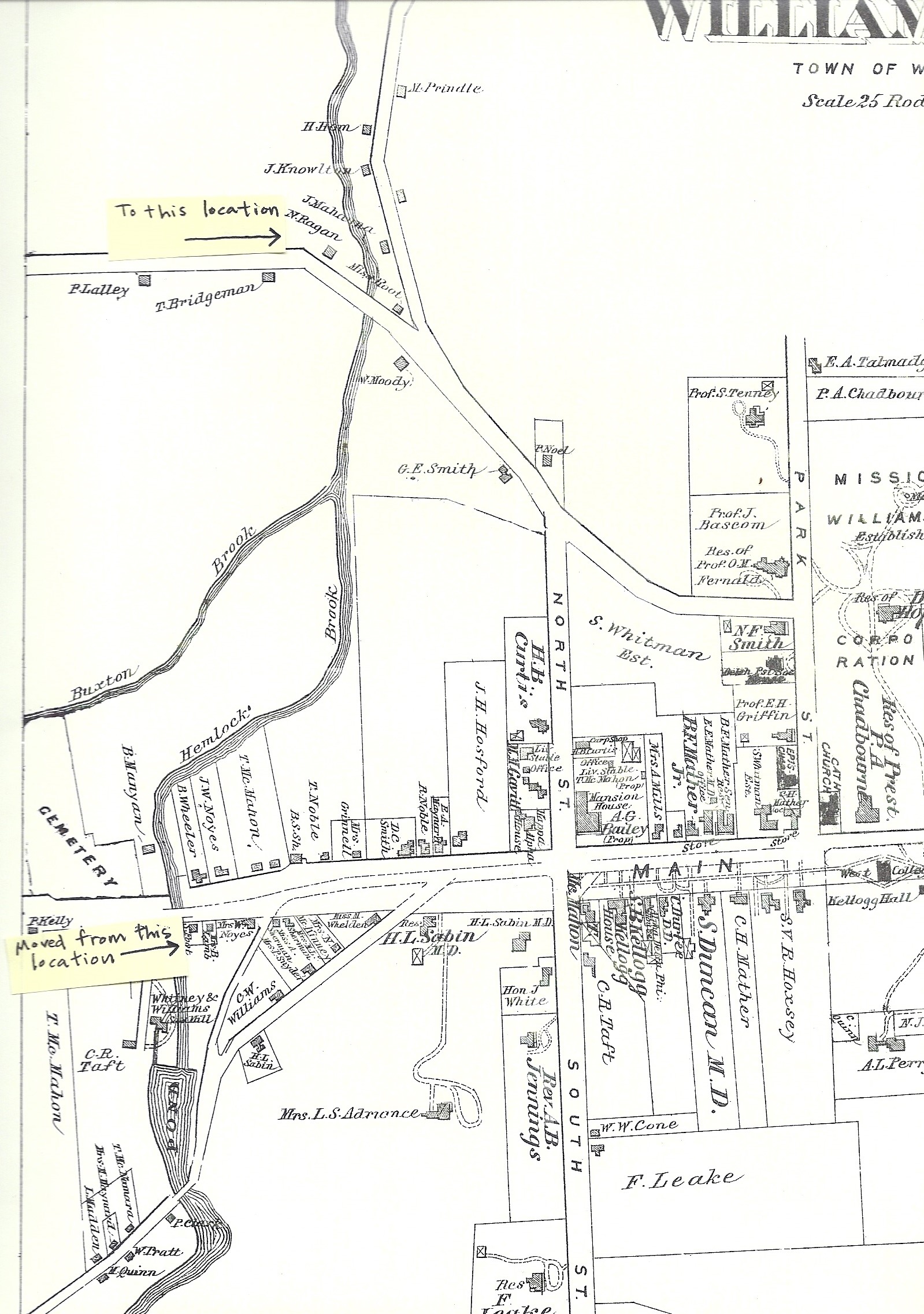

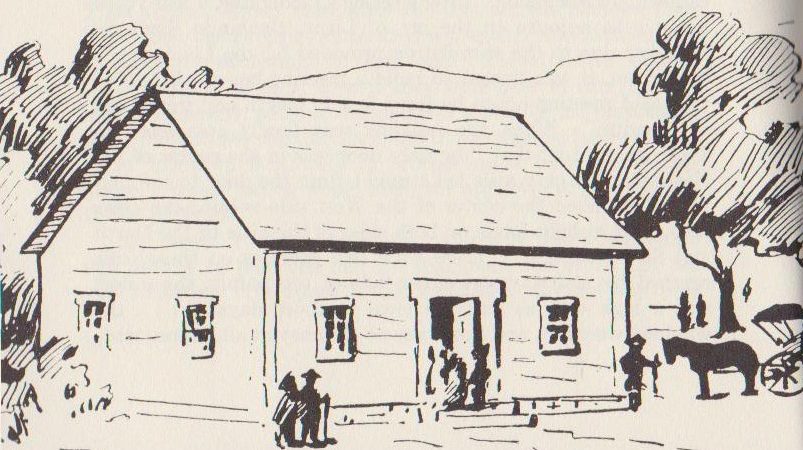

ALLEN CURTIS, the moderator of the meeting, was the only Proprietor not to have been a solider at Fort Massachusetts. He was born on May 18, 1708 in Wethersfield, CT and died in 1783 in Canaan, CT. He hosted the second Proprietors meeting at his home, which stood directly across Hemlock Brook from Seth Hudson’s house.

“Captain Curtis brought his military title from Connecticut, and after a couple of years carried it back there, where he honored it by a life of usefulness.” – Arthur Latham Perry, “Origins in Williamstown,” 1894.

“The infighting between the settlers of West Hoosuck…and the powers in Fort Massachusetts continued unabated…The continuing friction was most evident between natives of Connecticut, who were in the ascendancy in West Hoosuck, and the ‘Bay’ natives at Fort Massachusetts.” – Michael D. Coe, “The Line of Forts,” 2006 (See illustration of the line of forts.)

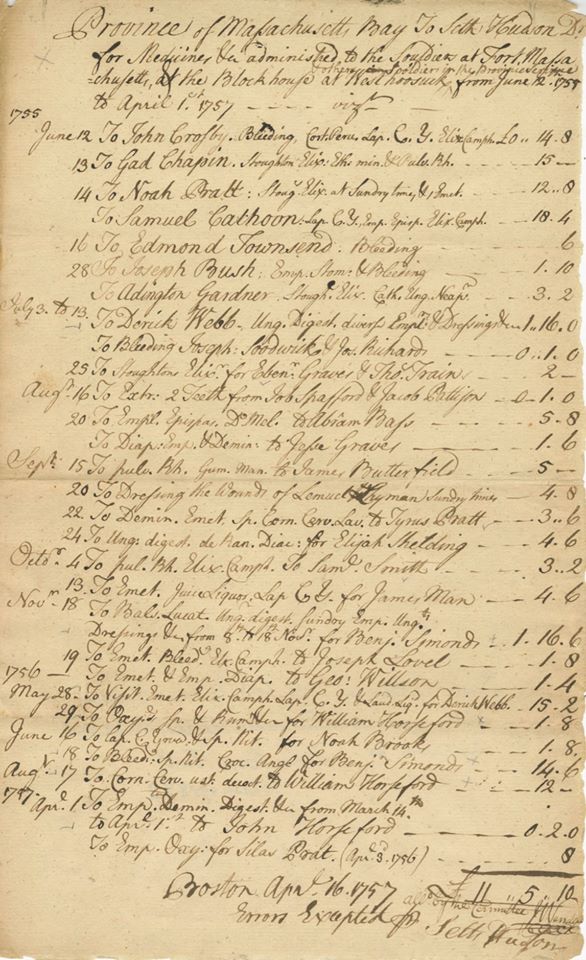

SETH HUDSON treated soldiers at both Fort Massachusetts and Fort Hoosuck. A bill for his medical services survives and is pictured here. He was very influential in the settlement of our town and the last survivor of the original proprietors. In 1756, upon the death of William Chidester, Hudson became the commander of the fort at West Hoosuck.

ISAAC WYMAN, the clerk of that first Proprietors meeting, was the second in command at Fort Massachusetts, having been appointed by Ephraim Williams, Jr.. Born January 18, 1725 in Woburn, MA and died March 31, 1792 in Keene, NH, he married Sarah Wells in 1754 in Deerfield, MA, where the first of their ten children was born. The second was born here in “Hoosuck, Massachusetts” and remaining eight were born in Keene.

“…during the decade of the 1750’s…rancor grew between Williams loyalists like Captain Isaac Wyman and an anti-Williams group led by Seth Hudson.” – Coe “The Line of Forts” 2006

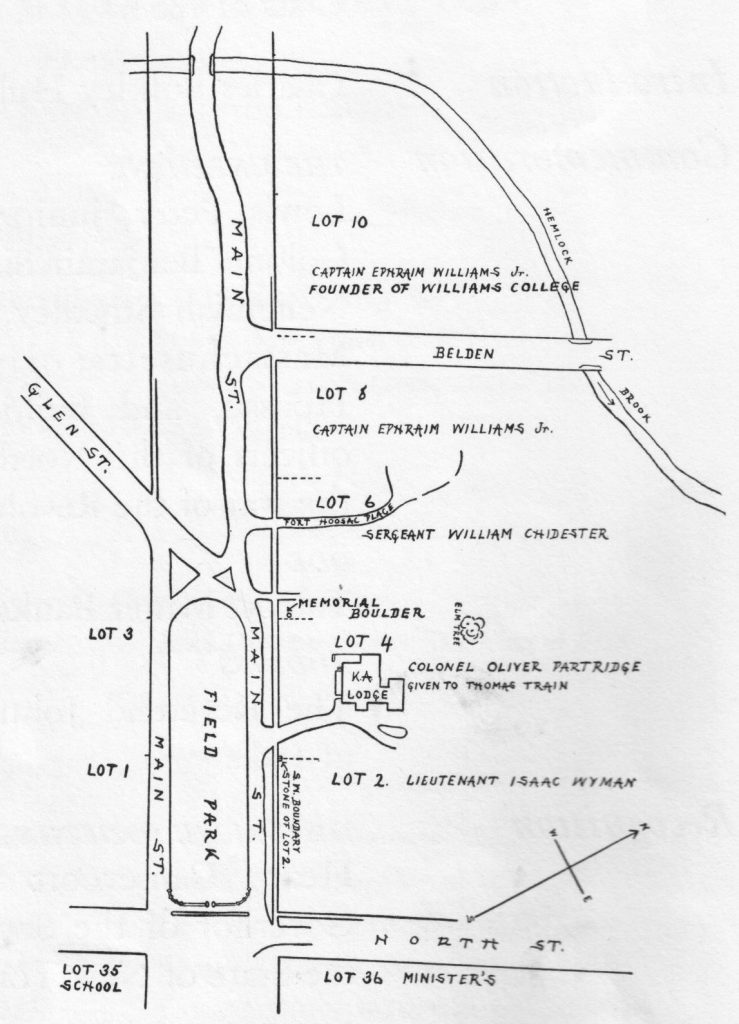

“Wyman…commenced [building] pretty soon on his lot, No. 2, which stretched along flanking North Street on the west side, and the front of which is now graced by the lodge of Kappa Alpha.” – Perry, Origins in Williamstown, 1894

“After 1759 [Wyman] continued to farm the ten acres surrounding Fort Massachusetts (acreage tat had originally been set aside for the use of the fort), but on November 13, 1761, he sold all his West Hoosuck property and moved to Keene.” – Coe “The Line of Forts” 2006

In 1762 Wyman opened a tavern on Main Street in Keene, which is now a museum (see photo). In 1770, the tavern was the gathering place for the first meeting of Dartmouth College’s Trustees. Although advanced in years, Wyman marched at the head of his company to Lexington in 1775, and later served in the Battle of Bunker Hill.

In “Origins in Williamstown (1894) Arthur Latham Perry wrote:” EZEKIEL FOSTER was from Fall Town, now Bernardston and quite constantly a sentinel in the line of forts from the beginning to the end. He drew house lot no. 13 in the original ‘lotting’ of West Hoosac…he was one of the first ‘eleaven families of us,’ already domiciled at West Hoosac, who petitioned Governor Shirley from Fort Massachusetts to which these families ‘ran for shelter upon the late alarm’ in October, 1754, for aid and military encouragement to ‘return to our settlements at the west town.’ Foster became a considerable landowner and a prominent citizen of Williamstown…”

Foster sold Lot No. 13 to Allen Curtis, another original Proprietor, but he “…continued a settler and citizen for many years. but bought lands, and had a home in different parts of town.”

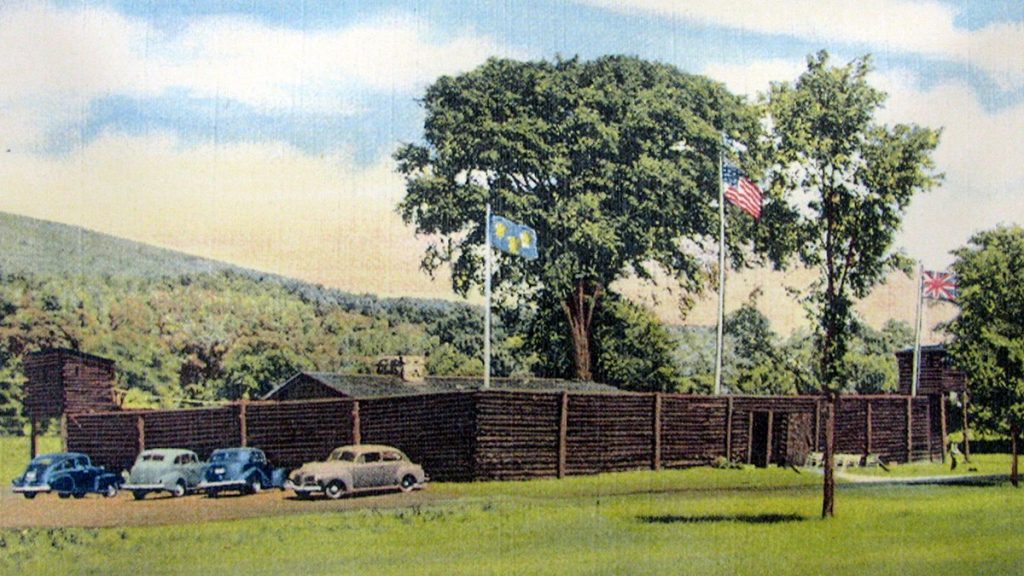

Thanks to Paul W. Marino for a comprehensive, illustrated look at Fort Massachusetts. Fort Massachusetts by Paul Marino

Postcard depicting 1930’s reconstruction of Fort Massachusetts.

JABEZ and GIDEON WARREN came from Connecticut via Brimfield, MA, and ended their lives in Vermont. Jabez was Gideon’s father, and another son, Jabez, Jr. also moved here, which adds to some confusion since our early records are incomplete.

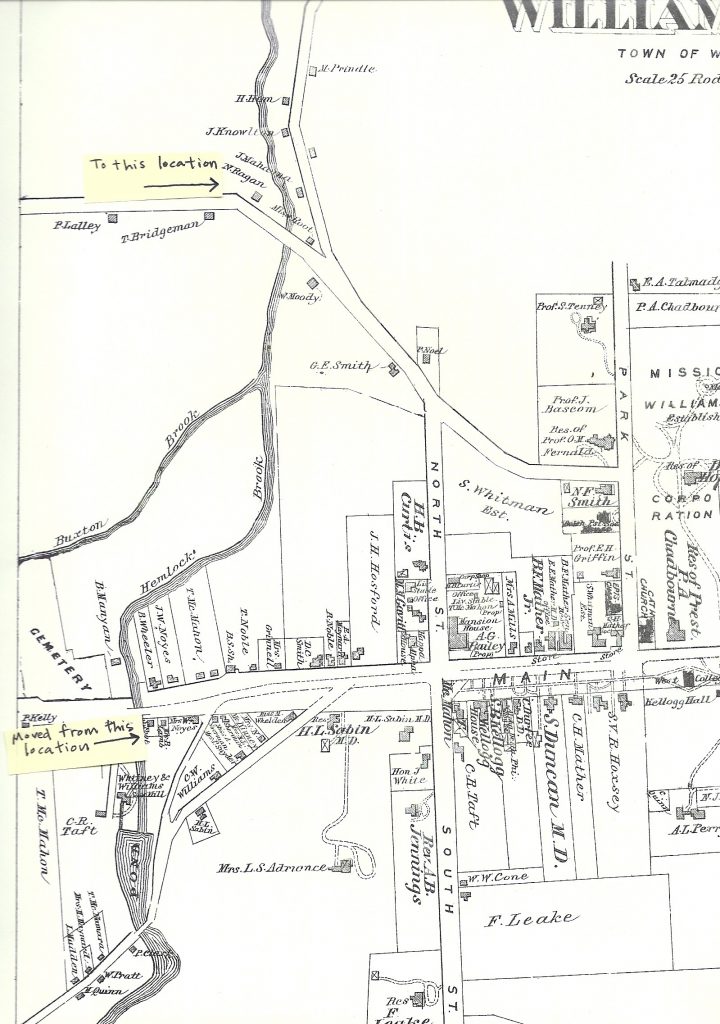

West Hoosac House-Lots with Proprietors’ names highlighted. From “The Hoosac Valley: Its Legends and Its History” by Grace Greylock Niles, 1912

Manuscript map by Albany surveyor John Rutse Bleecker, showing Fort Massachusetts and the Hoosick circa 1745-55, around the time Williamstown (West Hoosac) was settled. Chapin Library collection.

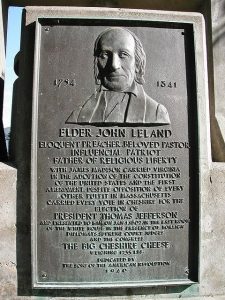

Here we meet some of our founding mothers for the first time, and encounter names – Blair, Meacham, and Simonds – which remain on our maps today.

JOSIAH DEAN was among the first European settlers to be granted land in what is now Hancock, and he may be the same man of that name to buy at auction in Boston the land that became the towns of Lenox and Richmond for £2,550.

His most significant action in West Hoosuck (Williamstown) was selling Lot 44 to Daniel and William Horsford of Canaan, CT, for “£260 Connecticut money old tenor.” That is the lot on which the Williams College Presidents’ house now sits. William and Esther Smedley Horsford became the second white couple to start a family in town.

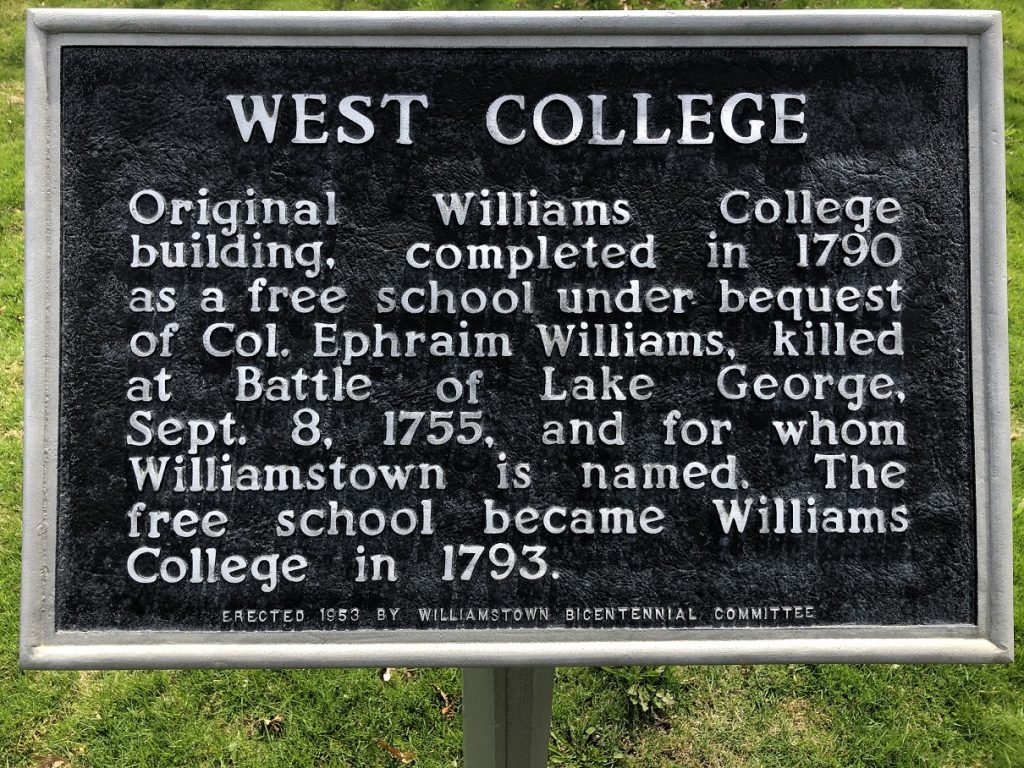

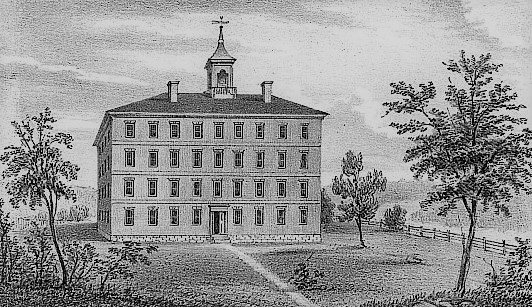

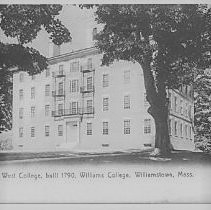

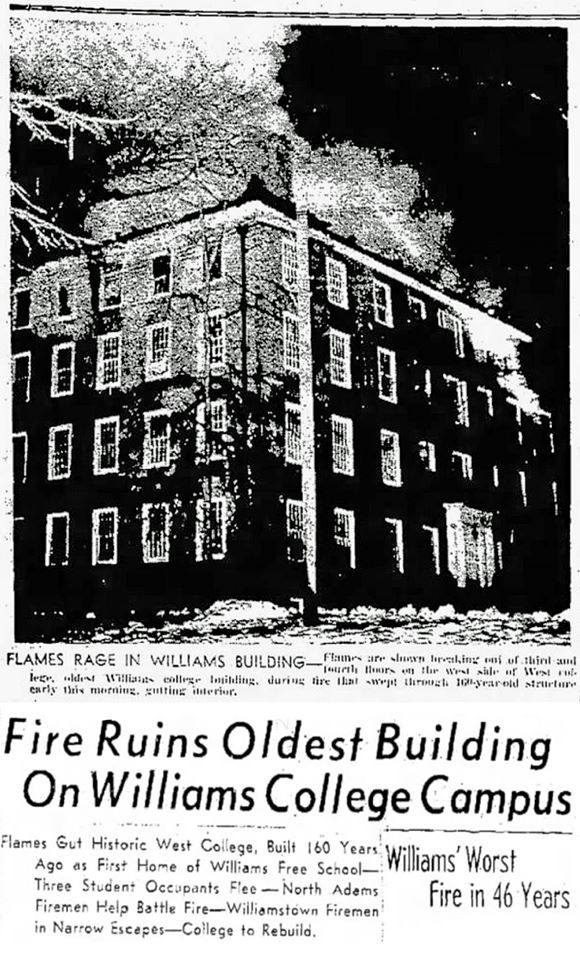

JONATHAN MEACHAM, originally from New Salem, MA, bought house lot No. 43 from Seth Hudson for £5, and built his home very close to where West College now stands. Meacham most likely encountered the same problems finding water that the college did, and so he moved to lot No. 49, close to what was called the “college spring.” Later he went to farm on Bee Hill, where many generations of the Hickox family later lived.

Meacham and his wife, Thankful Rugg, were original members of the church, but in February of 1779 a committee was formed “to wait upon Jonathan Meacham to enquire the reason of his absenting himself from communion.” The Meachams were not dismissed from the church, but “are designated among those ‘removed to distant parts.'” While his cousin, James Meacham, “left a large posterity which has continued to be identified with the town…Jonathan left none.”

Jonathan Meacham was with Ephraim Williams at the Battle of Lake George in 1755.

THOMAS TRAIN, born August 1727, was originally from Weston, MA. After an engagement went awry, Train enlisted and came to serve at Fort Massachusetts, where he drew house lot No. 30 in West Hoosuck, close by Benjamin Simonds and his family.

Although he was twenty-four years her senior, Train married 19-year-old Rachel Simonds, daughter of Benjamin and Mary Davis Simonds, the first child born to a European settler in town. They set up housekeeping on the southern slope of Townsend Hill (lot No. 63) where their daughter Sarah “Sally” Train was born in October 1772, exactly nine months after her parents’ wedding.

Before Sally was born Thomas Train had gone off to Virginia and acquired “a good title to some lands.” But on his return journey north he apparently died “and lies buried no one knows where.”

After two or three years of widowhood Rachel married Benjamin Skinner and Sally was raised with the children of that marriage. In July 1792 Sally married William Blair and died in 1864, at the age of 91 “universally respected and beloved.” Her tombstone in Westlawn Cemetery is pictured. Her husband, her son James, her mother, and many other family members are also buried in town.

The museum collection contains a linen sheet from the Blair farm. The flax to make the sheet was grown, processed, and woven in Williamstown by Maria Blair who was the daughter of Sally and William Blair.

Born in 1716 in Northfield, MA, Sergeant SAMUEL TAYLOR served at both Fort Massachusetts and West Hoosuck Fort, where he was the first commander, continuously from 1746-1757. His wife was with him much of the time and their daughter Susanna was born in Fort Massachusetts in 1754, and their son, Elias, in West Hoosuck Fort two years later. Elias Taylor was the first white male baby born in this community.

The year after Elias was born Seth Hudson recounts that Taylor was ordered by Isaac Wyatt to forcibly remove Jabez Warren and his family from rooms William Chidester had agreed they could occupy in his home. According to Hudson’s account, Taylor “…Halled out man, woman & Children Stole their Cloaths & broke to bitts & Destroyed some of Mr. Chidester’s goods…”Not surprisingly, Taylor moved his family out of town shortly thereafter.

Samuel Taylor was the first owner of lot No. 63 at the junction of Hopper Brook and the Green River, known as “The Crotch” or “Taylor’s Crotch” and now called Sweet’s Corners (see map). Ten acres there were set aside as a “Mill Lot.” After the Taylor family moved away, Asa Douglass of Hancock, the father-in-law of Samuel Sloan, purchased an interest in this lot. On October 15, 1767, the proprietors voted to grant William, John, and Peter Kreiger, a Dutch family who operated Kreiger Rock Mill in Pownal, “liberty to sett up a corn-mill and saw-mill at Taylor’s Crotch” before August 1st of the following year.

Water-powered mills of all varieties were vitally important to the growth of towns in the 18th and 19th centuries. Our most recent WHM newsletter contains a fascinating article on the early mills of Williamstown by Mary Fuqua. Early Williamstown Mills article.

EBENEZER GRAVES, was born March 15, 1726 in Hatfield, MA. He served at Fort Massachusetts from 1746-1752. Graves was one of the thirteen original settlers of West Hoosuck to build regulation house here between September of 1752 and September of 1753, having drawn lots Nos. 53 & 56. In January, 1753, he married Prudence Hastings of Greenfield, where the couple later settled and where Graves died on October 19, 1814, aged 88 years.

The original house in which the First Proprietors meeting took place was moved to Bulkley Street from the southeast corner of the Hemlock Brook bridge on Main Street via Hemlock Brook. The current address of the building (or what might remain of it within) is 56 Bulkley Street, and is drastically changed from the original regulation house.

The map below shows the path of the move of the Seth Hudson House down Hemlock Brook to Bulkley Street.

If you can find the site of the First Proprietor’s Meeting, and its marker, we hope you will send a picture to us at info@williamstownhsitoricalmuseum.org. For extra credit, can you find the “new” location of the house on Bulkley Street?