This week we will take a look at Berkshire County’s most famous suffragist, Susan B. Anthony. Although she only lived in Adams for the first six years of her life, her family roots run deep in the Hoosic Valley and she returned to the Mother City many times during her life to speak and visit relatives. Many members of the Anthony family still call this area home.

It was just before the beginning of the American Revolution that David Anthony and his wife, Judith Hicks, moved to Adams from Dartmouth, MA, bringing two little children with them (nine more were born here.) One of those two, Humphrey, married an Adams girl, Hannah Lapham. Daniel, the eldest of their nine children, born January 27, 1794, became the father of Susan B. Anthony.

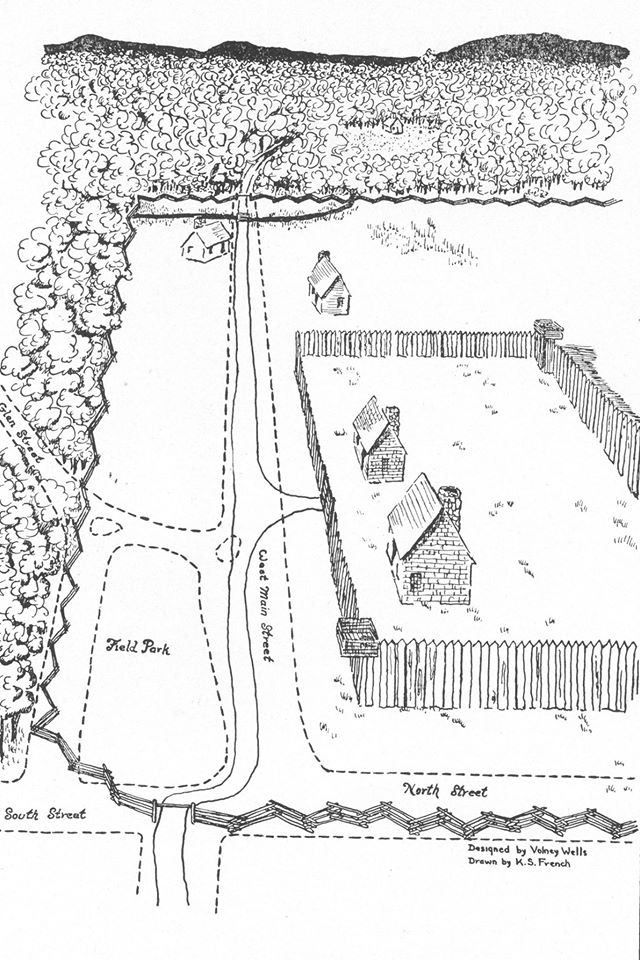

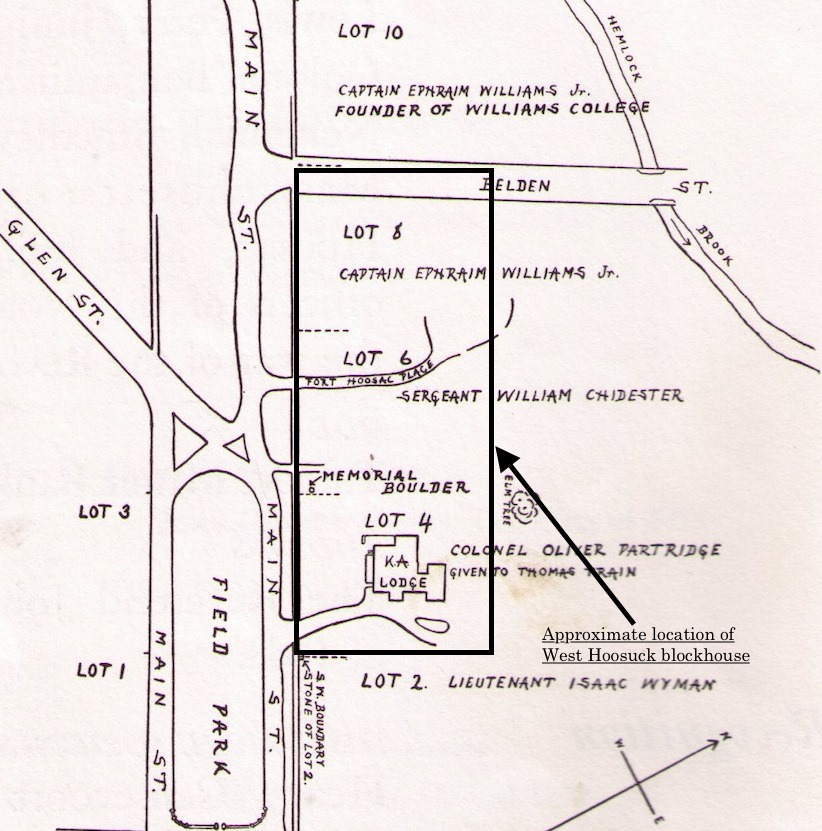

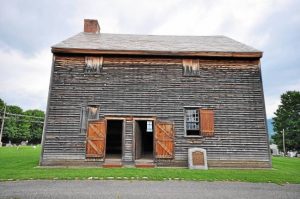

Daniel Anthony’s Birthplace

The Anthonys were Quakers. Susan’s mother’s family, the Reads (also spelled Reid and Reed in various sources), were Baptists and so their ancestors first settled in Cheshire rather than Adams, where Susan’s maternal grandparents Daniel Read and Susannah Richardson were married.

It was but a few months into this marriage when the first gun was fired at Lexington and the whole country was ablaze with excitement. Legend has it that when the minister asked at the end of the Sunday service who would volunteer for the continental army, Daniel Read was the first to step forward. What his new bride thought of this is not recorded, but they did not start their family until after Daniel had fought at Quebec under Benedict Arnold in 1775, at the capture of Ticonderoga under Ethan Allen, and under Colonel Stafford, of Cheshire’s Stafford Hill, at Bennington.

Susan B. Anthony’s mother, Lucy Read, was born on December 3, 1793, one of seven children. For many years the Reads were leading members of the Cheshire Baptists, led then by Elder John Leland, who had the idea of the Mammoth Cheshire Cheese which he presented to President Thomas Jefferson on New Year’s Day of 1802. But as the years progressed Daniel Read became more and more liberal in his beliefs and became a Unitarian.

Birthplace of Lucy Read, Susan B. Anthony’s mother

Birthplace of Lucy Read, Susan B. Anthony’s mother

Susannah Read “prayed the skin off her knees” that her husband would return to the Baptist fold, but he never did, and this precipitated the family’s move from Cheshire to the Bowen’s Corners neighborhood of Adams, where they bought land adjacent to the Anthony family.

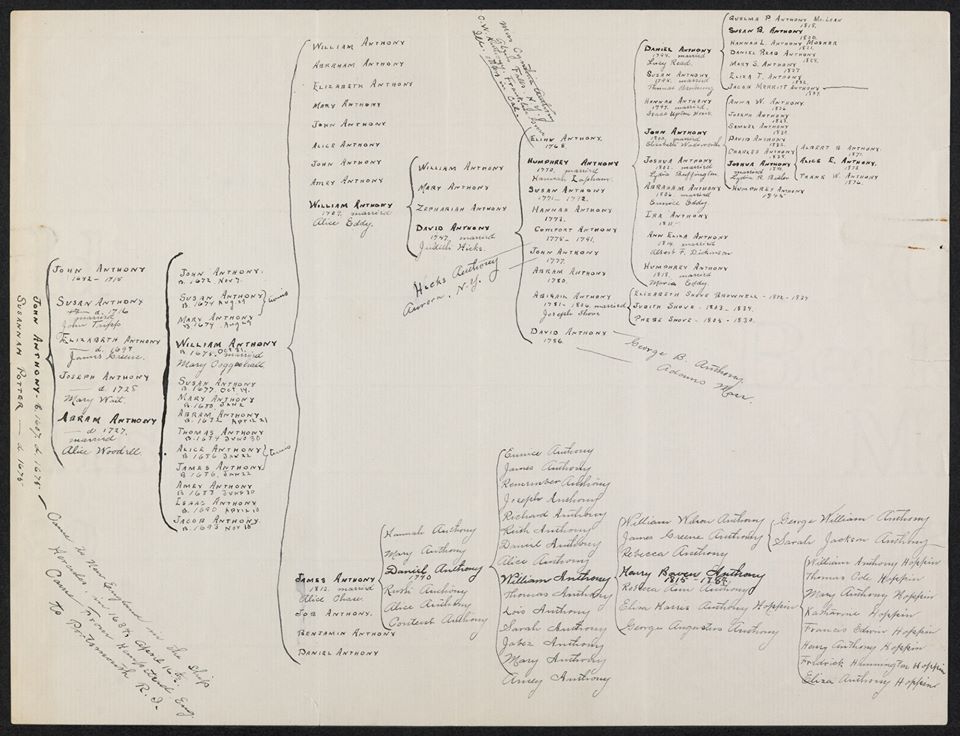

Handwritten Anthony family genealogy

The Bennington County History forum provided an interesting story: “Folklore tells us that Susan had a relative by the name of Peter Anthony. Peter Anthony was Quaker, a hermit who made his home on the western slope of a mountain outside of Bennington. One day he went out hunting and fell to death from a rock ledge. He was found many days later mangled, and frozen stiff. The Mountain was named Mount Anthony in his memory. Susan B Anthony was somehow related to him and visited Bennington in the 1850s to research family ties.”

… Continuing our look at Susan B. Anthony’s roots and how they affected her life’s work. In the 18th century there was a “state religion” in Massachusetts Bay Colony, and it was the Puritan faith that we now call the Congregational Church. As Quakers and Baptists, these families lived outside the norm in their own communities. This is why the Reads moved from the Baptist town of Cheshire to the “suburbs” of Quaker Adams when Daniel Read became a Unitarian.

The Quakers placed great value on education for both sexes and established schools that were attended by many neighborhood children. So while Daniel Anthony (1794-1862) was a Quaker and Lucy Read (1793-1880) was a Baptist, they went to school together. Daniel was sent away to Nine Partners, a Quaker boarding school in Dutchess County, NY, and returned to teach in Adams. It was a this point that romance blossomed between the neighbors.

But Daniel was forbidden to marry “out of meeting.” While the Quakers had what we would consider very progressive ideas about women’s rights and the abolition of slavery, they did not drink, dance, sing, or wear brightly colored clothing. With the exception of the drinking, Lucy Read was an outgoing young woman who enjoyed all of the above, especially singing since she had a lovely voice. She expressed the desire to “go into a ten acre field with the bars down” so that she could sing at the top of her voice.

So for her the decision to marry was the decision to completely change her way of life. On the night four days before their wedding she went out and danced until 4 am while Daniel sat quietly outside waiting for her.

Daniel then had to face the Quaker Elders when he and Lucy returned from their wedding trip in July of 1817. That his mother was an Elder and “sat on the high seat” undoubtedly helped the couples’ cause. While the Meeting contended that Daniel told them that he was “sorry he had married” Lucy, he insisted that he had said he was “sorry that in order to marry the woman I loved best, I had to violate the rule of the religious society I revered most.”

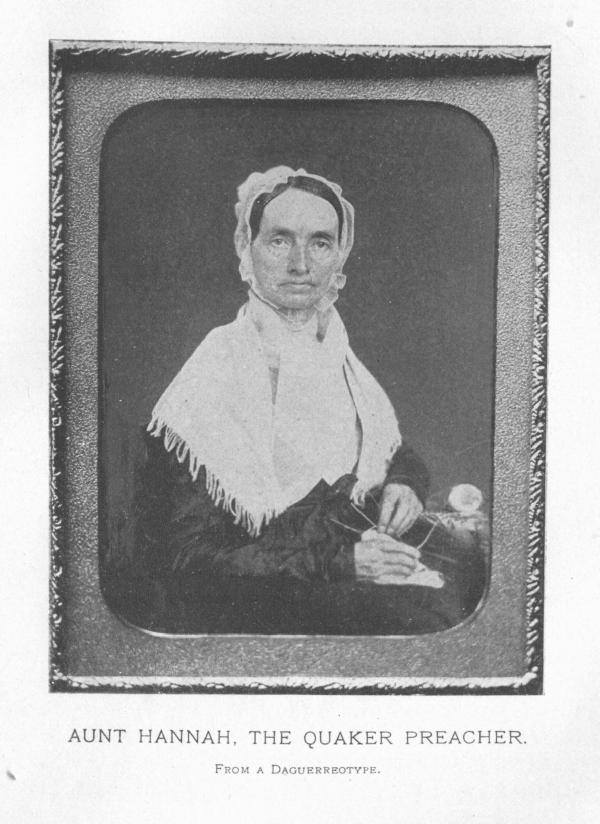

Hannah Anthony Hoxie, Daniel Anthony’s sister

Hannah Anthony Hoxie, Daniel Anthony’s sister

Susan B. Anthony was the second of Daniel and Lucy Read Anthony’s seven children. She was born on February 15, 1820, in the house that is now The Susan B Anthony Birthplace Museum on East Road in Adams. The home was built in 1818 by Daniel Anthony on land gifted to him by his in-laws, and adjacent to their property, with lumber given by his own father. Until that house was built Daniel and Lucy lived with her parents.

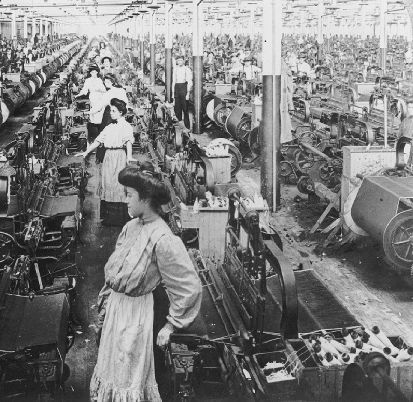

When the War of 1812 disrupted the importation of cotton cloth from England, Daniel Anthony was among the many businessmen who saw an opportunity. Hauling cotton forty miles by wagon from Troy, NY, in 1822 he built a factory of twenty-six looms power by water fed down from Tophet Brook through pipes made of hollow logs.

Millwork afforded “women of respectability” one of the first opportunities to earn money outside the home. And to preserve that respectability the millworkers, most of them young girls from Vermont, boarded in the home of the millowner.

Female mill workers in Pittsburg, PA textile mill, c. 1840s

Female mill workers in Pittsburg, PA textile mill, c. 1840s

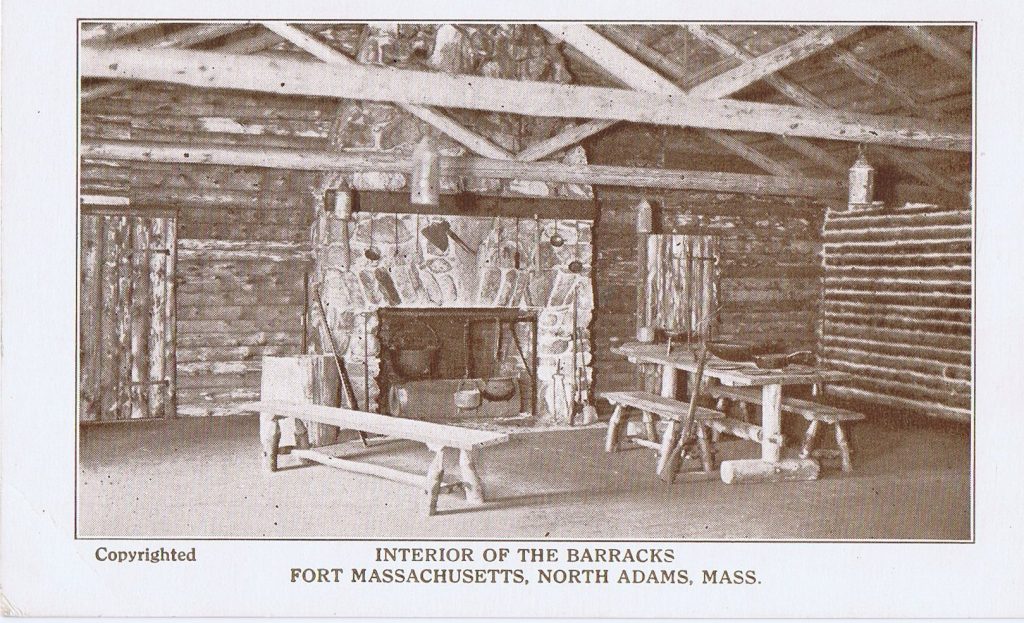

Lucy, with three children and counting of her own, boarded eleven of the millworkers with only the help of a thirteen-year-old girl who worked for her after school hours. She cooked their meals on the hearth of the big kitchen fireplace, and in the large brick oven beside it baked crisp brown loaves of bread. From a young age Susan was helping her mother in the house and questioning her father about why his female employees weren’t given equal pay for equal work.

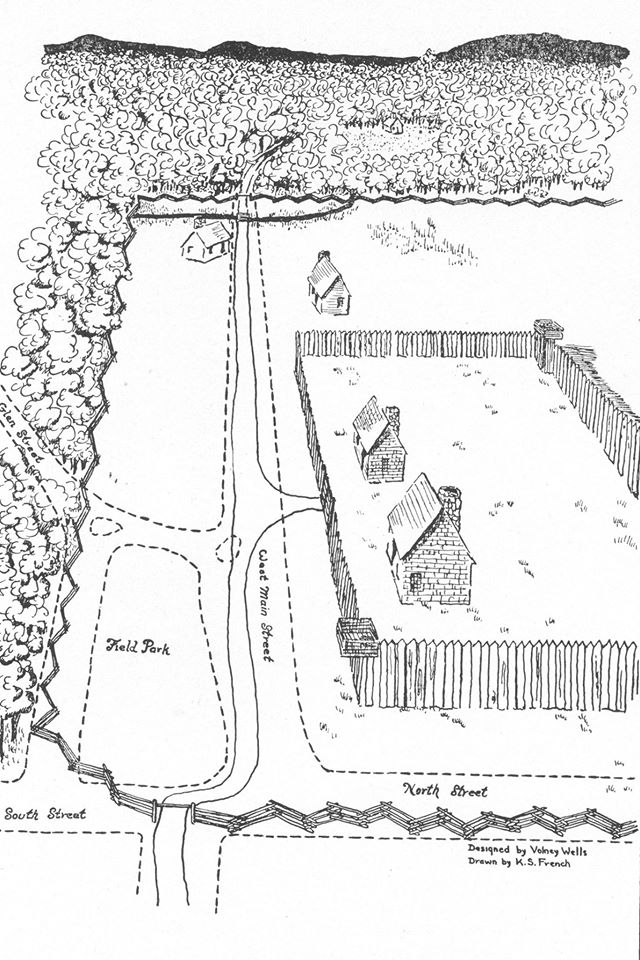

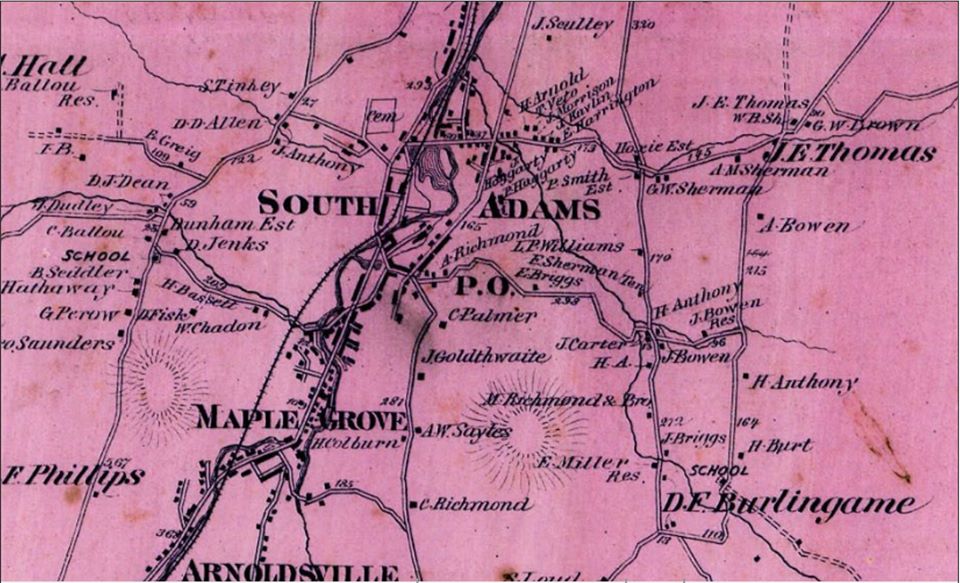

Homes still owned by Bowen and Anthony family members can be seen on the map below, clustered at the right. The two branches of Tophet Brook enclose the area, before running diagonally across the map (glancing off of the second A in ADAMS) to meet the Hoosic River downtown.

“Lucy Read Anthony was of a very timid and reticent disposition and painfully modest and shrinking. Before the birth of every child she was overwhelmed with embarrassment and humiliation, secluded herself from the outside world and would not speak of the expected little one even to her mother. That mother would assist her overburdened daughter by making the necessary garments, take them to her home and lay them carefully in a drawer, but no word of acknowledgement ever passed between them. This was characteristic of those olden times, when there were seldom any confidences between mothers and daughters in regard to the deepest and most sacred concerns of life, which were looked upon as subjects to be rigidly tabooed.”

– Ida Husted Harper, The Life and Work of Susan B. Anthony, Volume I 1898

Lucy Anthony gave birth to four of her eight children (six lived to adulthood) in one of the front rooms at what is now the The Susan B Anthony Birthplace Museum on East Road in Adams, MA.

Bedroom in the Susan B. Anthony Birthplace Museum

Their second child, Susan, was named for her mother’s mother Susanah, and for her father’s sister Susan. In her youth, she and her sisters responded to a “great craze for middle initials” by adding middle initials to their own names. Anthony adopted “B.” as her middle initial because her namesake aunt Susan had married a man named Brownell. Anthony never used the name Brownell herself, and did not like it.

The Quakers’ respect for women’s equality with men before God left its mark on her and as soon as she was old enough she went regularly to Meeting with her parents – her mother attended meeting but never became a Quaker because she felt she could not live up to their strict standard of righteousness – sitting by the big fireplace on the women’s side of East Hoosuck Quaker Meeting House in Adams. With this valuation of women accepted as a matter of course in her church and family circle, Susan took it for granted that it existed everywhere.

Daniel Anthony was a staunch Abolitionist, as were most Quakers, and he tried not to buy cotton for his mill that had been raised by slave labor. The cotton mill at Bowens Corners was very successful, and soon the family opened a store in one of the front rooms of what is now The Susan B Anthony Birthplace Museum in Adams.

Regarded as one of the most promising, successful young men in this region, Daniel soon attracted the attention of Judge John McLean, a cotton manufacturer in Battenville, NY, who was eager to enlarge his mills and saw in Daniel an able manager. Despite their parents’ distress at seeing the young family move 44 miles away, in July of 1826 Daniel, Lucy and their children climbed into a green wagon with the Judge and his grandson, Aaron, and headed northwest to Washington County.

The first year the Anthonys lived in Judge McLean’s house where there were two slaves not yet manumitted. The Anthony children had never seen black people before and Anthony’s father explained that in the South they could be sold like cattle and torn from their families. Susan was saddened by their plight.

Before she became a champion for women’s rights and suffrage, Susan was very active in the Abolitionist movement, circulating anti-slavery petitions when she was 16 and 17 years old. She worked for a while as the New York state agent for the American Anti-Slavery Society. She first met Elizabeth Cady Stanton after Stanton had attended an anti-slavery meeting at Seneca Falls. When her family moved to Rochester, NY, in 1845 she became life-long friends with Frederick Douglass.

Susan’s adult life and work are well chronicled and we encourage you to learn more during our Summer of Suffrage as we celebrate the centennial of the passage of the 19th amendment giving women the right to vote. Although she had died 14 years earlier, the amendment was known as the Susan B. Anthony Amendment and there is no doubt that American women owe a great debt of gratitude to this daughter of the Berkshires!

The Williamstown Historical Museum is planning to open to drop-in visitors on Saturdays from 10 – 4 starting this coming Saturday, July 25. Social distancing guidelines will be followed, and masks/face coverings will be required for visitors and staff. We are also open by appointment if you wish to visit outside of our open hours. You may call 413-458-2160 or email sarah@williamstownhistoricalmuseum.org to set up an appointment to visit or carry out research. We look forward to seeing you soon!

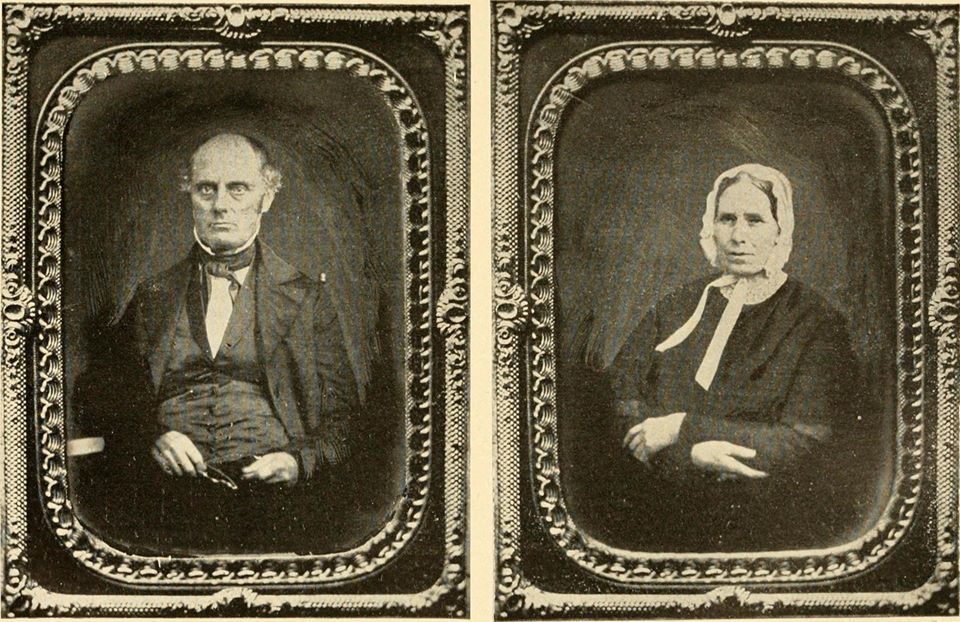

Daniel and Lucy Anthony

Daniel and Lucy Anthony Quaker Meetinghouse in Adams

Quaker Meetinghouse in Adams

Quaker Meetinghouse interior

Quaker Meetinghouse interior