We hope you have had a peaceful, almost summer, week and that you were able to find last week’s site, Riverbend Farmhouse and Tavern, located on Simonds Road.

This week’s site is a bit more difficult to locate, though it is located near the center of the town’s commercial district.

The building in question is just one of several houses in town to contain remnants of an original “regulation house.”

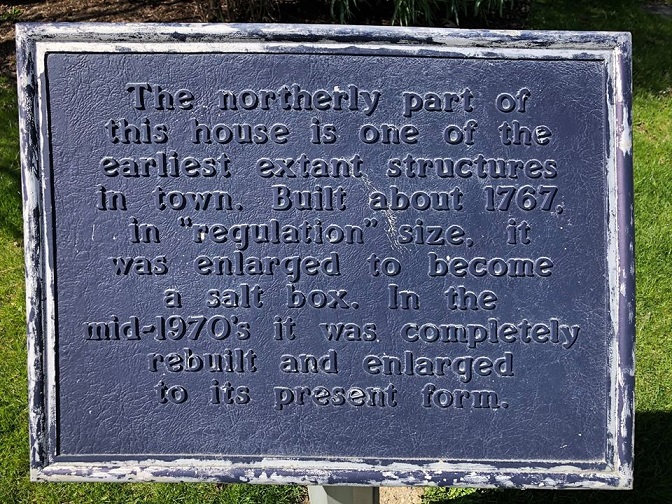

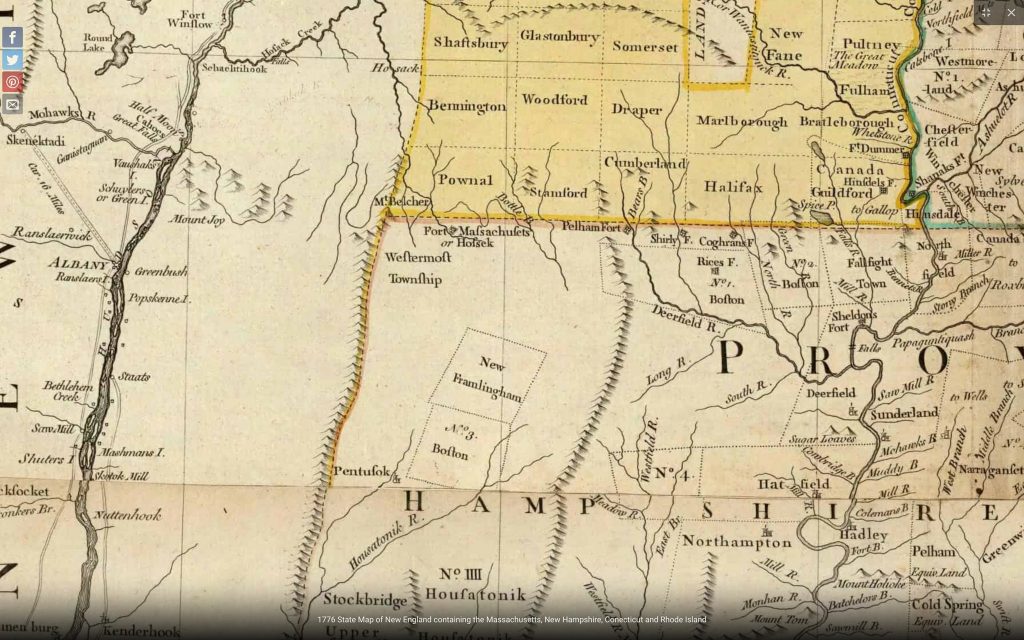

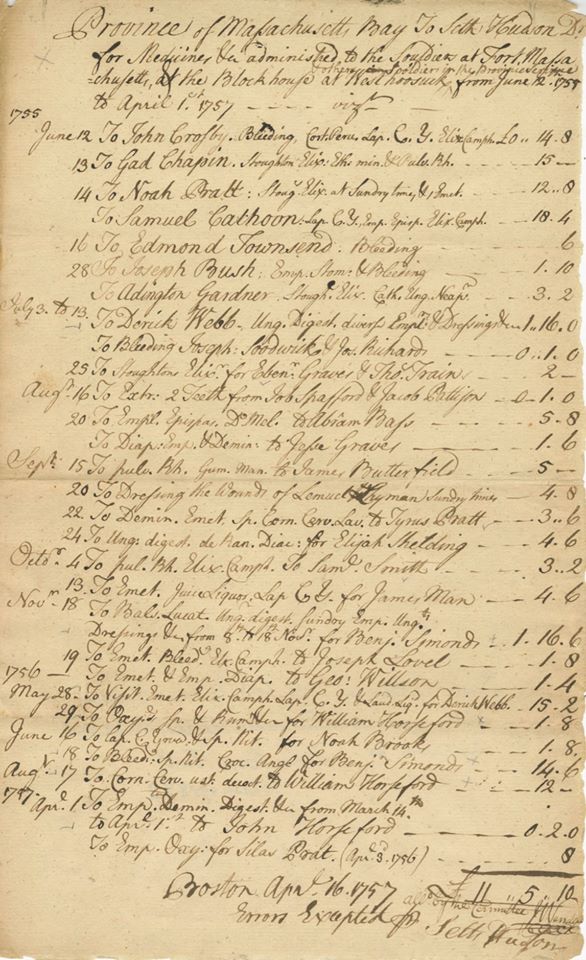

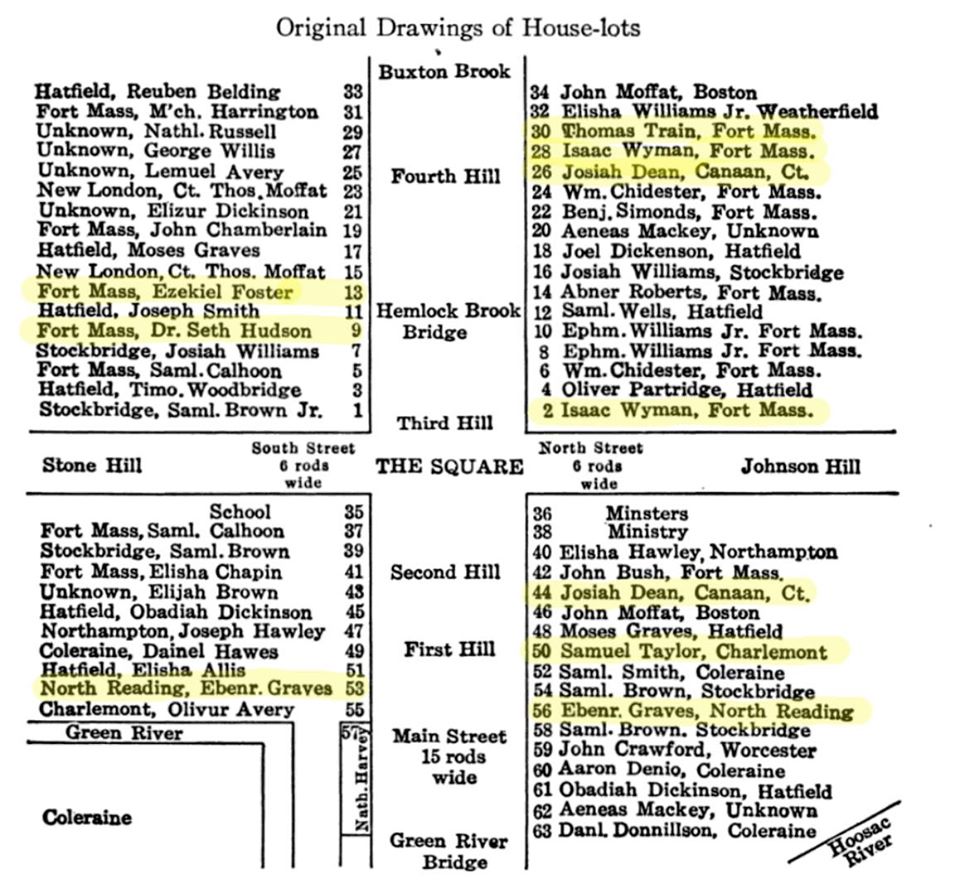

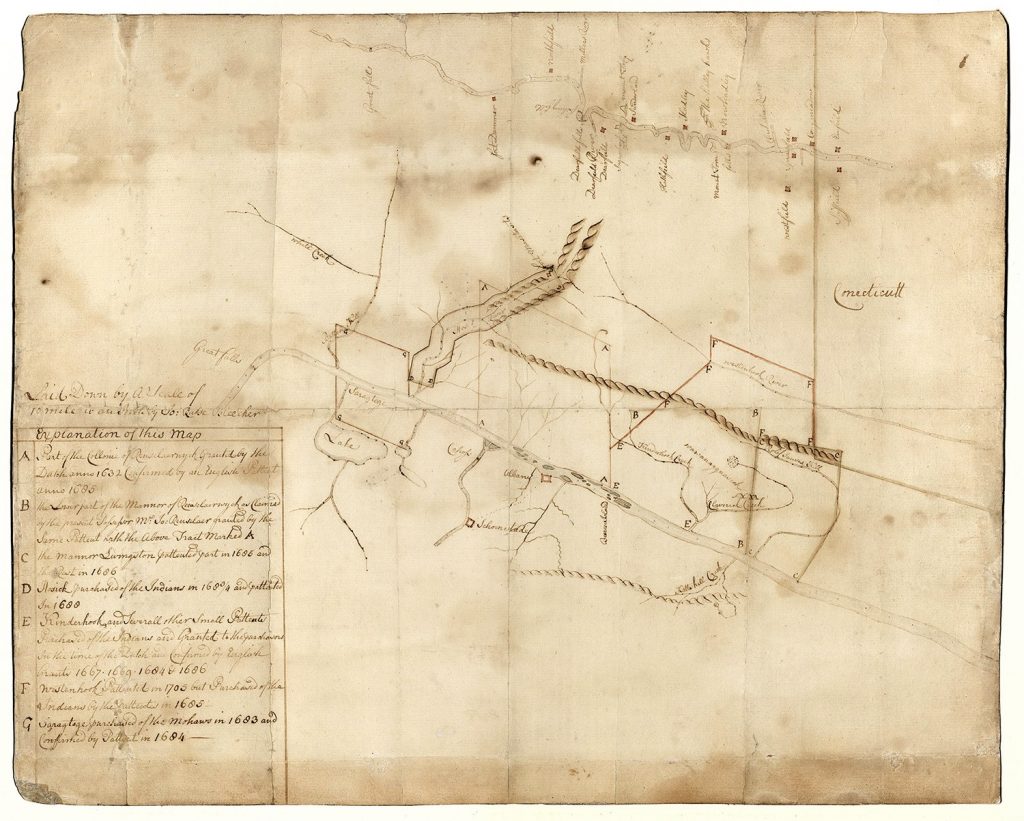

What was a “regulation house”? In the 1750’s, when the British crown colonized this area, only white men were able to “own” land. Land in what became Williamstown was sold by the Massachusetts Bay colony to these men through a lottery and they had to quickly erect a building on the site to stake their claim. A regulation house was the smallest structure you could build to satisfy that requirement. The settlers then built larger homes around that original structure.

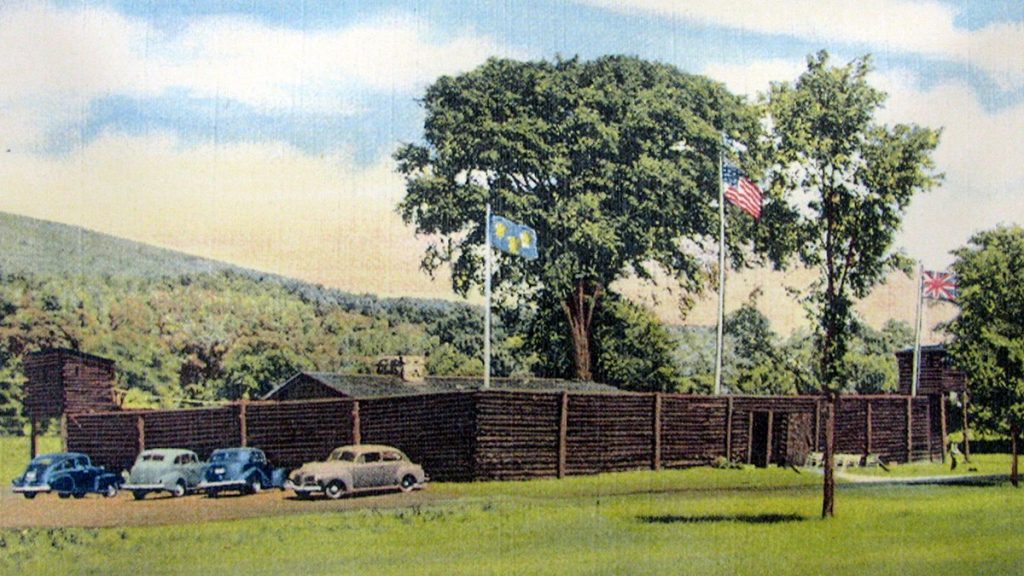

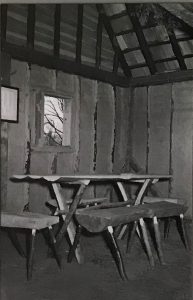

The 1753 House on Field Park is a replica of a regulation house. It was built by volunteers using 18th century methods and tools to celebrate the 200th anniversary of the first proprietors’ meeting in 1953. The photos below show the construction process and the building’s interior. A visit to 1753 house is a must if you are spending time in Williamstown!

This week’s historic site is a structure that contains the frame of a regulation house built around 1767. The timbers of the regulation house lie fairly deeply buried here, and this is not the only building in town to contain remnants of a regulation house.

You can tell just looking at the outside of the 1753 House, such a building would have been cramped quarters for even a couple, let alone a large colonial era family. But the regulation houses were just the first step in staking claim to a land grant, and our earliest landowners were soldiers from Fort Massachusetts and the West Hoosuck Fort. Even if they were married and had children, it was unlikely that their families were with them here in the “wilderness” at first.

A regulation house was never intended to be a home. It was a quick structure to establish land ownership that would then be expanded to house a family. There are several homes in Williamstown that started life as regulation houses.

Thanks to Michael Miller for an inside look at our historic building for this week, which used to belong to his family. His comments have been edited to keep the location of the marker and the building a secret. Have you found it yet?

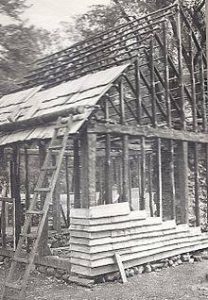

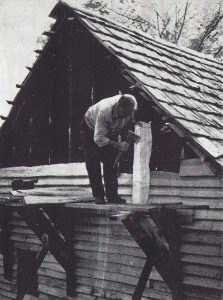

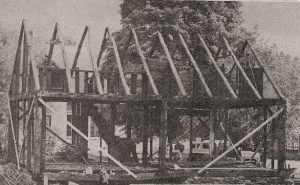

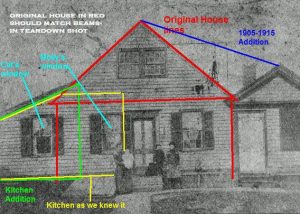

“The only part of the original home, owned since the 1870s by my great-grandparents, grandparents, and lastly my parents, is the smaller portion on the north side. In the “tear-down” photo you can see the original beams of the ‘regulation house’ that remains.

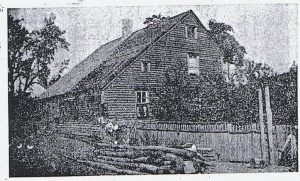

Following the “tear-down” photo you see the original house (with additions marked in color by Mike) from around 1900, followed by the same photo without the markings, and then a view of the building in its saltbox configuration.

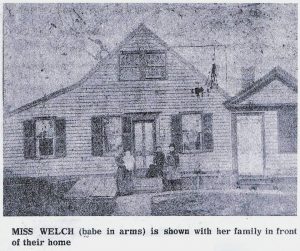

From Mike: “The ‘babe in arms’ is my great aunt Catharyn Welch, born in 1899…Our family owned all the corner lot and the next two lots heading west…(former Norton and Los properties).”

From the Collection of James and Michael Miller, c. 1973

From the Collection of James and Michael Miller, c. 1973

Thanks to our friend and neighbor Dick Steege for this article “The Life of a House” explaining how and why regulation houses were built and expanded over the centuries in our community.

The Life of a House by Dick SteegeFrom the Massachusetts Cultural Resource Information System (MACRIS) records of the Inventory of Historic Assets of the Commonwealth and National Register of Historic Places for The Massachusetts Historical Commission (MHC) 1998:

The structure presently at *** Street…is a recent recreation of 18th-century domestic architecture which incorporates into its fabric framing members of an authentic ca. 1770 residence…

During the comparatively peaceful period between the close of the Seven Years War and the onset of the Revolution, settlers streamed into Williamstown. In 1765, 285 residents inhabited 54 houses; by 1770, the population had doubled, and 30 more houses were erected. By 1774, Williamstown’s 1,015 residents occupied some 137 houses. Many of those newcomers were drawn from points south, and many were artisans who brought specialized skills to the village economy.

One of those men was cordwainer Isaac Searle, who came to Williamstown from Northampton and erected a portion of this house about 1770. Subsequent occupants included the families of Enos Wells, Joseph Osborne, William Touser, George Goodman, Norman Nichols (like Searle, an artisan; Nichols was a jeweler), and Electa Drury.

In the mid-19th century, the property passed to the family of blacksmith Michael Welch, who moved to Williamstown from Pownal, Vermont about 1868, and established his residence here, as well as a thriving shop just north…at the foot of Cole Hill.

In the late 1880s, Maggie Welch, like many women who at the turn of the century desired an occupation that would not require them to work out of the home, opened a dressmaking establishment here, assisted by her sister and neighbor Mary Welch Pike as well as Kate Donahue and Nellie Madden.

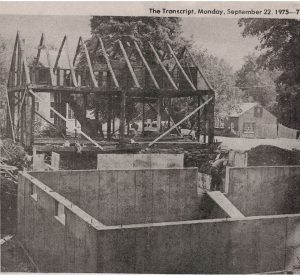

The house remained in the Welch family until the 1970s, when it was purchased by Bruce Grinnell for his offices. In 1975, the building underwent major alterations.

The Mass. Historical Commission Survey also details the 1975 overhaul of the “oldest house in town” and the North Adams Transcript covered the controversy surrounding it. Have you located the building and the historic marker yet?

“The structure presently at *** Street…is a recent recreation of 18th-century domestic architecture which incorporates into its fabric framing members of an authentic ca. 1770 residence. The newest sections of the building recreate the appearance of a two-story, side-gable, 4/4 center-chimney, Georgian-era dwelling with a on- and-a-half story rear ell. Window and door surrounds on the Latham Street facade are pedimented. Double-gable dormers are set into the one-and-a-half story ell roofline. The 18th-century framing materials are largely found in the northernmost section of the present building, today a wide, three-bay, center- chimney structure with its gable end…

In 1975, the building underwent major alterations. Nineteenth and 20th-century additions and alterations to the ca. 1770 structure were stripped away, until only the frame of the original building remained. The new and much larger building, designed by Twanette Garvey, incorporated the original post and structure into an “ell” on the north (rear) facade…The larger, two-story section was entirely new.”

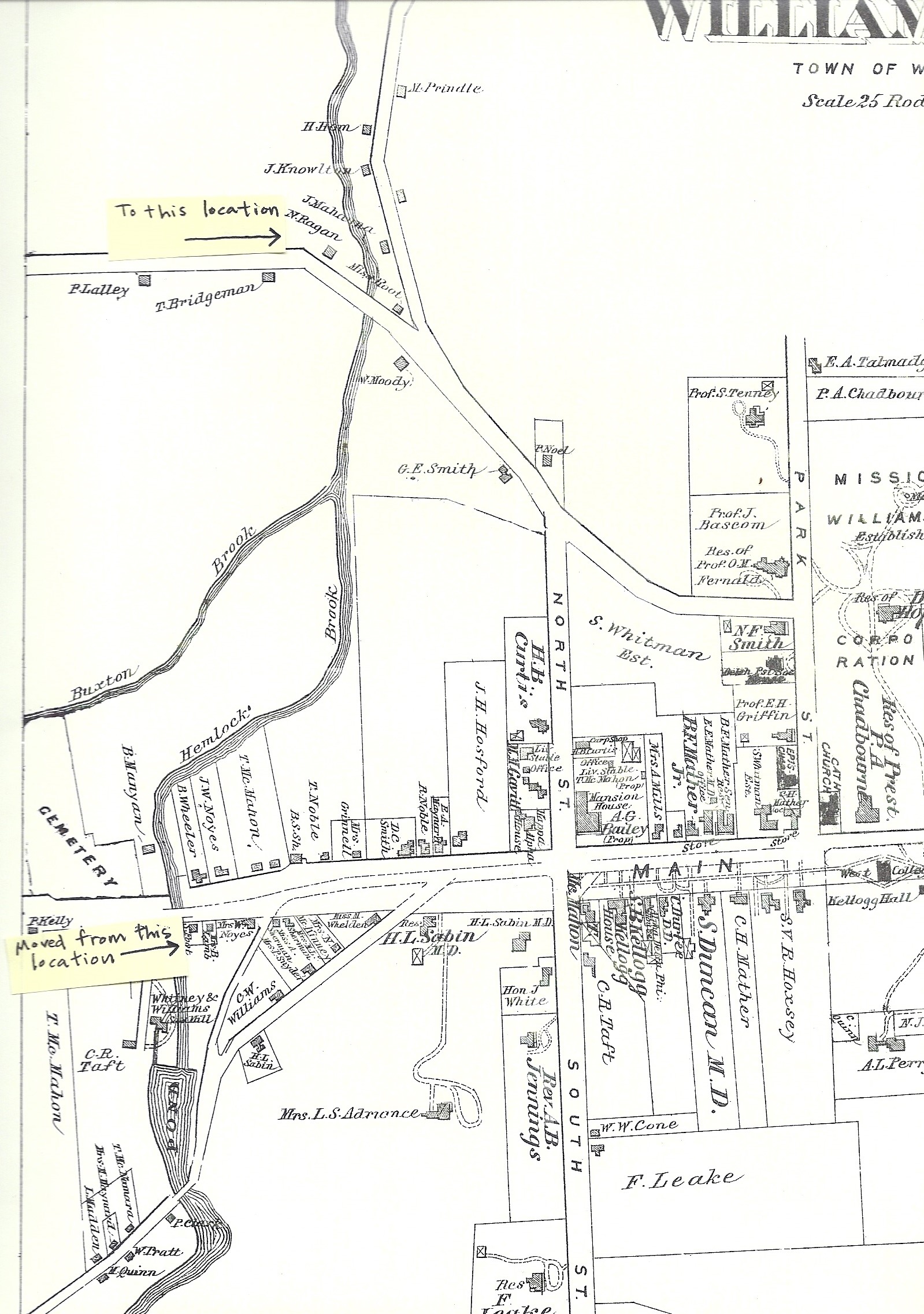

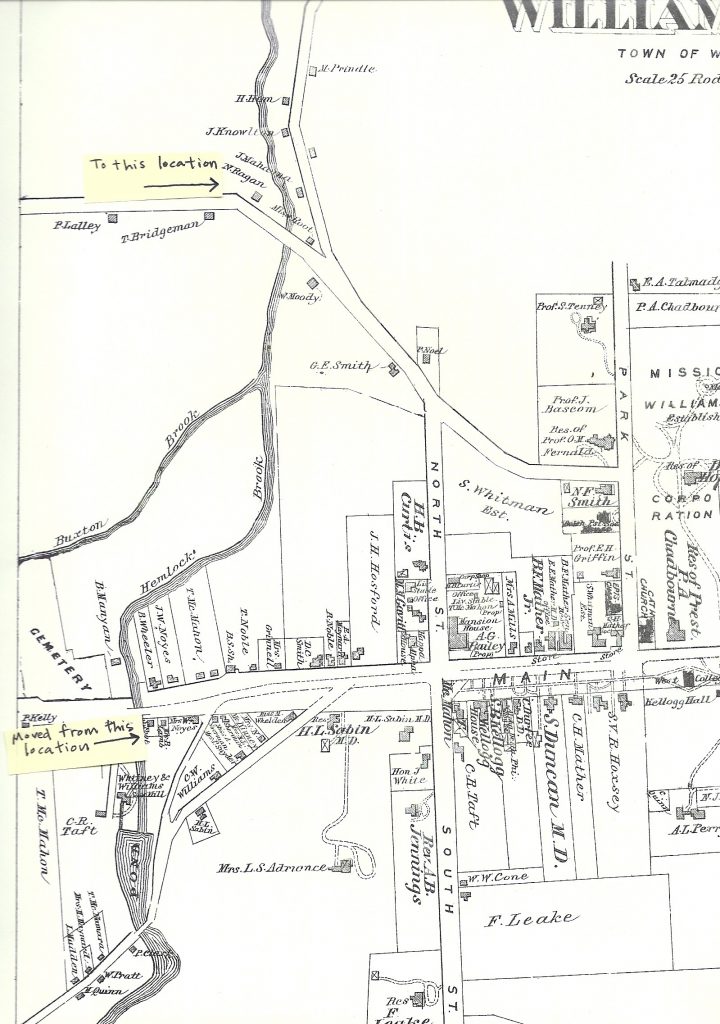

Have you spotted this week’s historical marker at the corner of Latham and Water Streets? It is the northernmost portion of the house that faces east on Water Street that contains the timbers from the original 1770 regulation house.

There are many other homes in town that contain remnants of regulation houses or other colonial era structures. Here are photos of just a few of them. Take a drive down West Main Street, around the town center, and down Water Street/Green River Road to South Williamstown and keep your eyes open!

Final words from the Massachusetts Historical Commission:

“This property has been altered to the extent that its material integrity has been severely compromised. Its location and early history, however, would qualify it to contribute to the potential Town Center Historic District. The Town Center Historic District is a potential historic district that began to develop ca. 1765 and continued to the present as an industrial, commercial and working-class residential area. The district is important as the gathering place for groups from every section of the community that contributed to Williamstown’s labor history and civic development, as well as its social and recreational life.”

1136 Main Street

1166 Main Street

1174 Main Street

1192 Main Street

Have you found the site and its marker, located at 95 Water Street, at the Corner of Latham and Water Streets? If you find it, we encourage you to photograph the building and its marker and email the images to the Williamstown Historical Museum at info@williamstownhistoricalmuseum.org so we may add it to our current day images of the town’s historic sites. Thank you!