It’s the start of the museum’s Summer of Suffrage! In this series and online exhibit, with the help and generous contributions of research from The Northern Berkshire Suffrage Centennial Coalition, we will celebrate the 100th anniversary of the ratification of the 19th Amendment. We will look at the Woman Suffrage movement, its progress in the region, key suffragists, and women who have made a difference since the 1920 ratification of the 19th Amendment.

Massachusetts residents played a significant role in the Woman Suffrage movement, and author Barbara Berenson wrote an accessible and informative book, titled Massachusetts in the Woman Suffrage Movement. We encourage you to learn more about the book by clicking on the image below to go to the webpage for the book and you can click on the button below to hear an audio interview of the author.

Radio Interview with Barbara Berenson

Phoebe Jordan

Berkshire County’s second most famous suffragist is Phoebe Sarah Jordan (1864-1940) of New Ashford, MA, and yet few County residents know who she was, why she is noteworthy, or have seen a photo of her, even though there are people still alive today with childhood memories of her.

Her current claim to fame is that she was the first American woman to legally vote in a presidential election in November of 1920, after the ratification of the 19th Amendment. But that is not the headline on her Berkshire Eagle obituary.

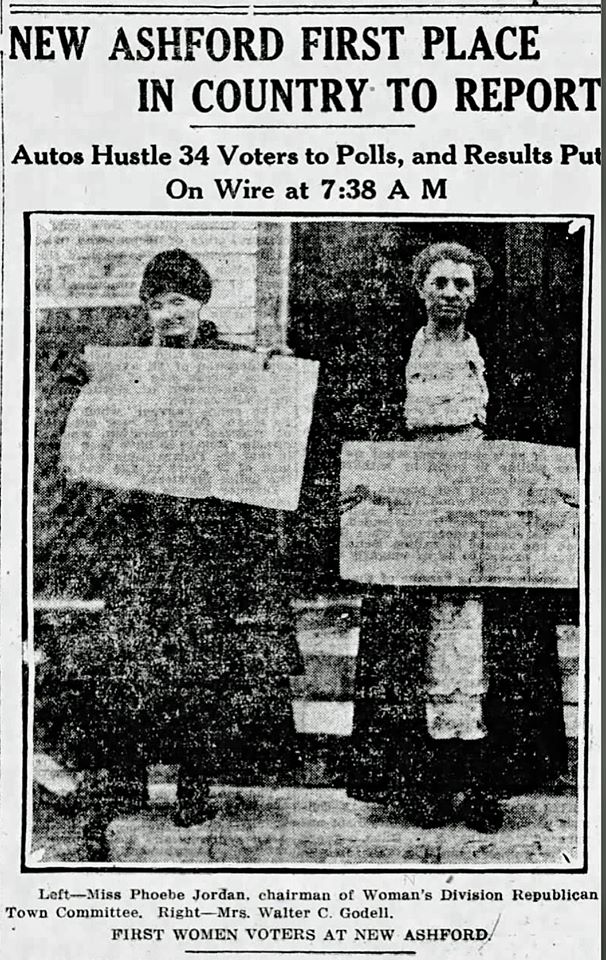

For five national elections, from 1916-1932, New Ashford was the first town in the nation to cast its ballots (Dixville Notch, NH, usurped that honor at the 1936 election) thanks to a publicity scheme cooked up by Dennis J. Haylon, managing editor of the Berkshire Eagle, and Carey S. Hayward, city editor of the Pittsfield Journal, to open the polls in what was then the Commonwealth’s smallest town, at 6 am. With the cooperation of the three dozen or so voters, it was possible for New Ashford to be the first community to report election returns.

Boston Globe, November 3, 1920

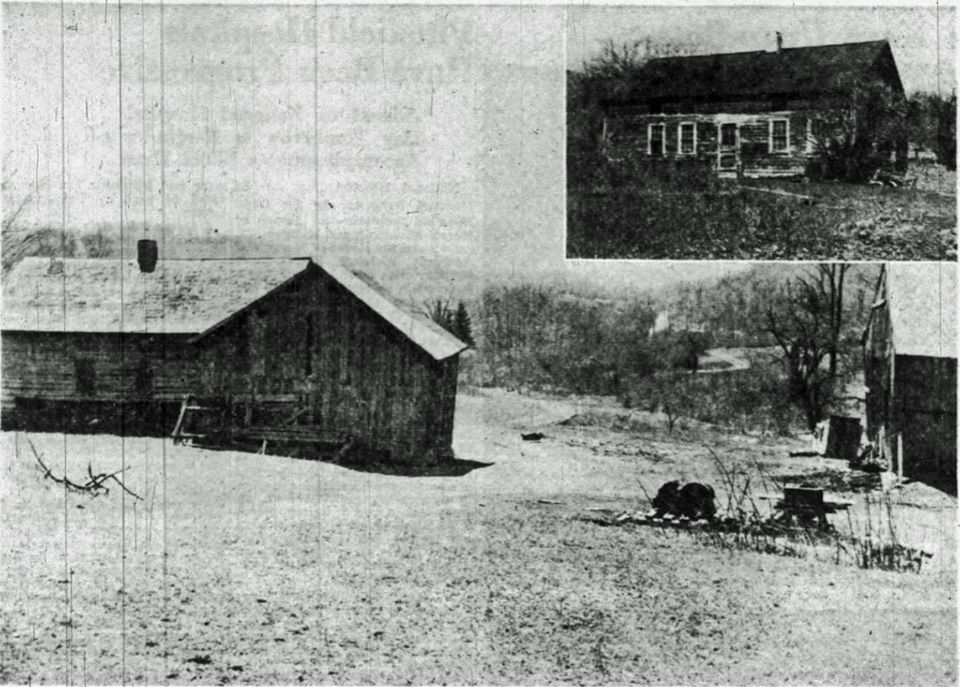

Elections were held in what was then the schoolhouse on Mallery Road – since restored and known as the 1792 Schoolhouse, and since automobiles – not to mention paved roads – were still a novelty in 1916, many voters, including Jordan, arrived on foot.

Photo montage of New Ashford 1792 schoolhouse, Beatrice Nichols Phelps, Warren H. Baxter and Phoebe Jordan in a Berkshire Eagle retrospective article August, 1955.

1792 Schoolhouse, New Ashford

1792 Schoolhouse, New Ashford

iBerkshires photo of the alumni of the 1792 Schoolhouse at the opening of the restored building in November 2016

Who was this first American woman to legally cast a vote in a Presidential election?

Phoebe Jordan was the quintessential New Englander. Born to Emily Middlebrook and Sidney Deloss Jordan in Washington, MA, on February 26, 1864, she came to New Ashford to live with her aunt, Miss Josephine Jordan, when she was seven and never left.

Her grandfather, Francis Jordan, had arrived in New Ashford in the early 19th century. All the town’s farmers gathered to help him “raise” his house in May of 1831.

When other family members passed away Phoebe Jordan came to run the farm, which eventually grew to 400 acres. Though weighing not more than 100 pounds she did much of the work herself, having no more than two hired men to help her.

She was an expert at operating a horse-drawn mowing machine and in the winter she operated a similarly powered snow plow. She raised prize winning turkeys. She supplied the schoolhouse with its annual allotment of firewood. She was an expert marksman and killed a fox caught robbing her chicken coop with one shot at a distance of 102 feet. She never married.

For 12 years she was the owner and operator of New Ashford’s sole non-agricultural industry – a charcoal kiln, one of the last in the County – until the top of the cone caved in after a big snowstorm in 1931, burying 15 cords of hardwood.

Like her Aunt Josephine before her, she drove her heavily-laden two-horse farm wagon 12 miles to Pittsfield to sell her charcoal and farm produce. Her personal vehicle was an 1870 single-horse carriage, but her trek to the polls was usually made on foot.

So it is no surprise that this most independent and resourceful woman was a suffragist!

We are told Jordan was a suffragist, but our local newspapers at the time carried little news of local suffrage efforts, beyond running cartoons skewering women’s demands for full enfranchisement.

We do know that, long before she could vote, she was the chair of the New Ashford Republican Committee, proving that women were actively involved in politics alongside the men before the passage of the 19th amendment.

And she was a big supporter of the PR stunt that made New Ashford the first town in the nation to vote and record its election results, so it was only natural that, as soon as she could vote, she showed up bright and early at the polls.

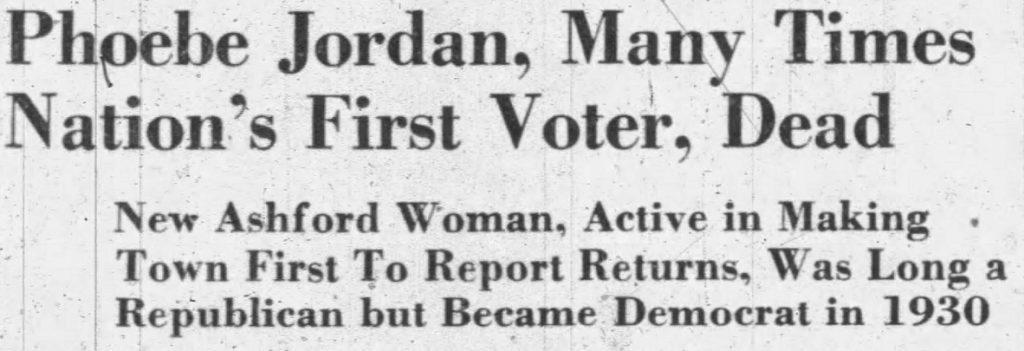

We saw that when the Boston Globe featured a photo of Jordan and another New Ashford woman who were the first to vote, the news wasn’t that they were women, but that they were the first citizens in the USA to vote in the 1920 presidential election.

The following year Jordan enthusiastically ran for a seat on the New Ashford Board of Selectmen – and garnered exactly one vote. Women may have been grudgingly welcome at the polls but not in the seats of power.

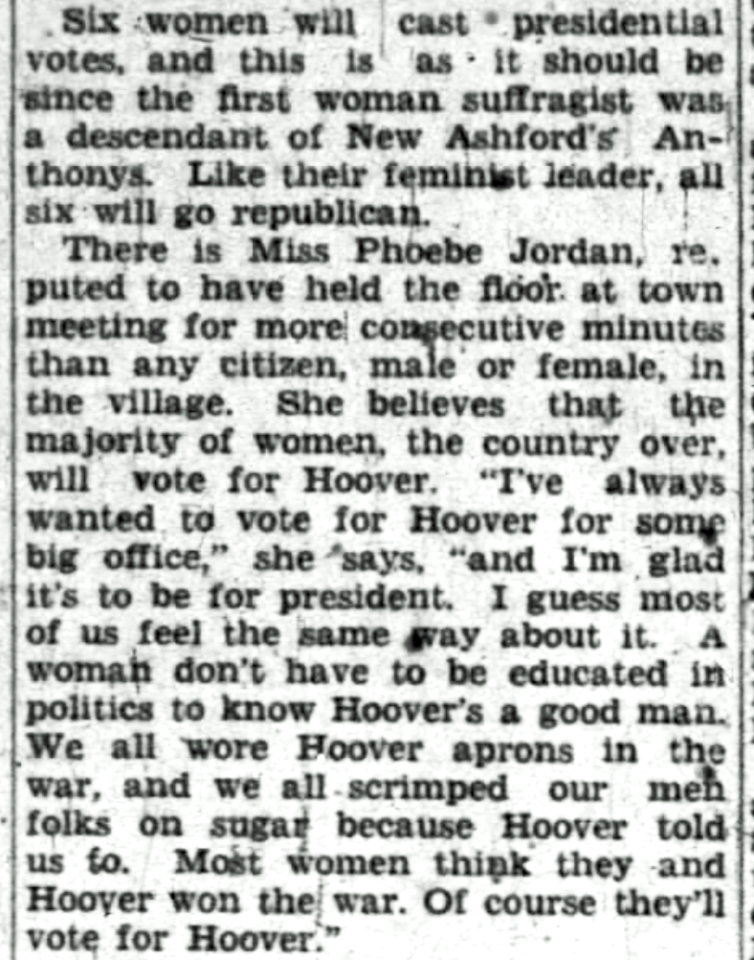

Still she continued to be a staunch Republican (see the clip from the Berkshire Eagle in July of 1928 below in which she explains at length why women support Herbert Hoover) until, in 1934, she “became dissatisfied with the manner in which the Republicans were running the state and the nation and left the party flat” after which she became “as firm a Democrat as she was a Republican” according to the North Adams Transcript.

When Jordan died in 1940 her obituary in the North Adams Transcript hailed her as the first person in the nation to cast their ballot in four consecutive presidential elections – 1920, 1924, 1928, and 1932.

It wasn’t until 1992 that she was publicly identified as the first woman to vote legally in a presidential election. And it was the effort, started in 2008, to raise money to restore the 1792 schoolhouse in New Ashford, that really began to capitalize on this feminist claim to fame for the building and the town. And it worked – in 2016 the town cut the ribbon on the restored schoolhouse and invited all living alumni to attend the ribbon-cutting ceremony.

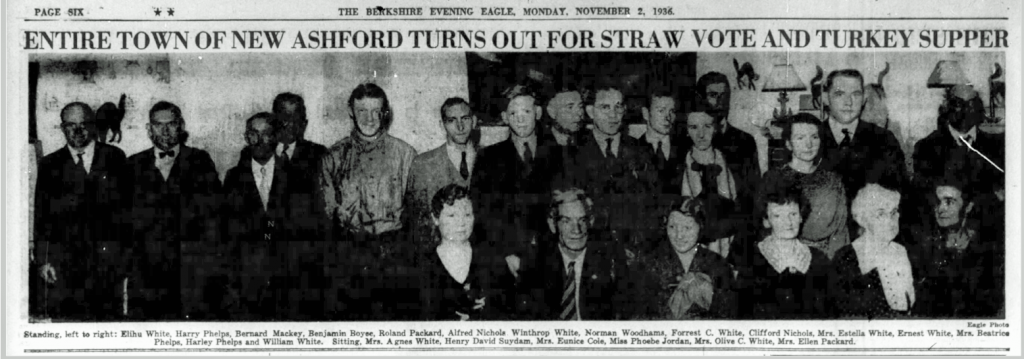

The voting population of New Ashford turned out for a turkey supper and straw vote in advance of the 1936 presidential election, the first in which Dixville Notch, NH, usurped their status as first town in the nation to vote. Phoebe Jordan is seated in front, third from the right. The Berkshire Eagle 11-2-1936.

Do you have Suffrage stories to share? We hope you will let us know if any stories were passed down from the women in your families. Email Sarah at sarah@williamstownhistoricalmuseum.org to tell us your story.